Listen or Die

Audio is so integral to Alien: Isolation’s suspenseful gameplay, it demands the player keeps their ear cocked for survival.

Story: John Broomhall

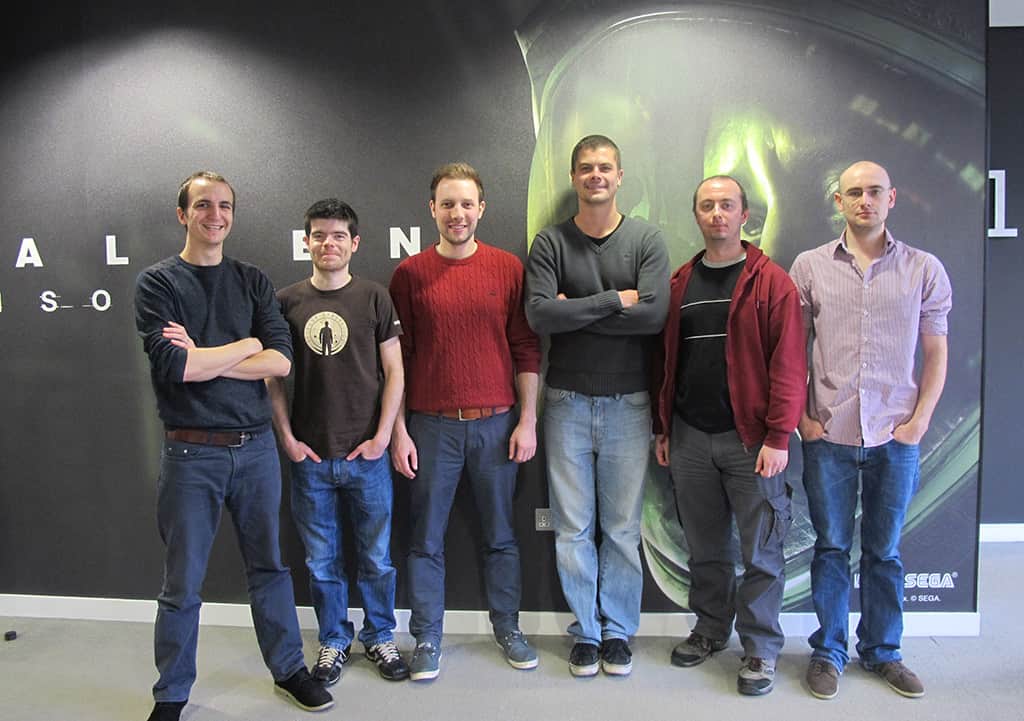

Extreme unease, spine-chilling suspense, oppressive fear, sudden terror — all in a day’s work for Byron Bullock, James Magee, Haydn Payne and the rest of their audio team who, over the last two years, have had the gratifying vocation of peddling audio anxiety for a living.

The critically lauded, yet terror-inducing fruit of their labour is Creative Assembly’s horror title Alien: Isolation. It’s a videogame incarnation of a world set in a time just after Ridley Scott’s Alien. The movie was famed for harnessing the power of sound to frighten the living daylights out of moviegoers, but hearing an alien walk the same Sevastapol space station corridors knowing it’s hunting you, that invokes a new level of fear. It’s so scary, players recording YouTube walkthroughs of Alien: Isolation, who know they’re not actually in the game themselves, spend hours in a virtual crouch position peering out of doorways and over in-game furniture listening for the sound of their tormentor.

KILLER SOUND

Byron Bullock: I’ve never played another game that encourages you to think about audio so extensively. The alien uses sound as a primary hunting sense, so you always need to be thinking about how much noise you’re making. We even track your real-world sound using the Microsoft Kinect and Playstation camera hardware, so if you scream on your sofa you’ll give away your position in-game!

You’re constantly questioning if it’s safe to run. Are you going to attract the alien if you use a weapon? Plus sound can work to your advantage as a distraction — say deploying an IED or just hitting things with your claw axe. Imagine your way is blocked by a group of hostile humans. Make some noise, then hide whilst the alien comes and rips that group apart for you! Of course, now you have to safely evade the alien yourself.

We encourage players to listen carefully; sound is one of your greatest weapons and best lines of defence. It can tell you how far away the alien is, if it’s in the vents or on the same level as you. Its vocals can communicate its awareness and the motion tracker reveals any movement around you with a familiar and disconcerting blip.

AT: Did you define an overall ‘audio style guide’?

Bullock: The art direction was tagged LoFi SciFi, a term used to describe the analogue, push-button world of Alien. The game is set just after the events of Ridley Scott’s 1979 movie, one of the first to portray space in this used-up, industrial ‘truckers in space’ way. It’s a time of CRT monitors; no holograms or flat screens. This obviously dictated the audio direction, everything needed to have that tactile feel and lo-fi vibe. Some of the most iconic sounds in the film are things like the mechanical ticks and beeps of the ship’s AI.

AT: How does the audio in a game like Alien: Isolation actually operate?

Bullock: We can play around 100 voices at any one time. A voice is one sound, a footstep for example, a door close or a dialogue line. This may sound like a lot but a gunshot might be made up of multiple voices; the main shot sound, mechanics like the trigger, a 5.1 reverb and reflection tail, bullet drops, low frequency sweeteners, projectile flight, impact sounds, the character’s clothes, a vocal reaction and any other effects like ear whine. It adds up!

We can place sound in the game-world in real-time, attach sounds to objects that move, and mix all those voices live at run-time using various real-time DSP like EQ, compression, limiters, etc. We can script logic to determine how and when sounds play and deliver mono through to 7.1.

Game sound is very non-linear, highly interactive and dynamic compared with film. In film you know exactly what’s about to happen; you can set up moments, and sculpt the sound-scape around them. That’s very hard to do in a game. Mostly you don’t know if and/or when an event will trigger; so you have to create systems, rules and logic that work dynamically.

This is especially true in a game as interactive as Alien: Isolation. We aimed to sculpt audio the same way you would in a film to create the high tension and suspense so crucial to horror — but we had an unpredictable, cleverly adaptive alien AI using its senses to hunt the player down. It could hear the player, see the player and any light emitting from their torch. This was a problem for the sound department. We needed to know when the alien would attack and preempt that moment in order to build suspense and tension.

WWISE CAGE MATCH

James Magee: We have several audio systems at work, designed to enable an immersive, reactive and dynamic sound experience, responsive to this emergent gameplay.

We used Audiokinetic’s Wwise sound engine and developed bespoke tools to interface with it. Scripting was done through a powerful in-house game editor developed for the project called CAGE. This gave our sound designers the same tools as the level designers, enabling complex visual scripting and access to real-time data to drive the sound.

One of our most significant audio systems was based around the concept of sound networks, a way of intelligently and automatically sub-dividing the world into different acoustic spaces. Sound networks were primarily a means of ‘cheaply’ calculating high-quality Obstruction/Occlusion, but also allowed us to attach parameters to run other environmental systems such as reverb and ambience.

Our AI systems also made use of sound networks to affect logical sound representations, meaning they ‘heard’ sound in the same way as the player. We made use of this through Stealth and Threat parameters calculated from the AI’s awareness level. For example, as the player makes noises the alien can hear it based upon the surrounding environment.

This real-time data was incredibly useful in driving many RTPCs (real-time parameter controls) within Wwise to emphasise mix elements, eg. bringing the sounds of the main character Amanda and the alien to the fore while ducking or filtering ambient sound to create focus and anticipation in certain moments.

MUSICAL LAYERS

AT: How do you integrate music soundtrack in a world where environmental sounds are so important to the gameplay?

Bullock: We constantly assessed how each sound would make the player feel. That often meant sounds would take on tonal and sometimes musical characteristics.

Early on, we made a conscious decision not to have wall-to-wall music. That’s not to say we didn’t like the music — our composers did a fantastic job! — but we wanted the soundtrack to have contrast and dynamics. You don’t get used to music playing, so it has impact when it does.

Some of the best audio moments are quiet ones without music — you walk into a dark corridor, it’s all quiet except for something moving in the dark. All you can hear is yourself, the walls creaking and some unexplained movement, it’s really tense.

Also, sound can add a sense of realism which can shock people. The sound of the alien ripping apart someone as they scream loudly from the other end of a dark corridor will instantly put you on edge. That moment doesn’t need music — it would feel less real.

Magee: Using parameters such as Stealth and Threat, plus ‘Obstructed_Distance_To_Alien’ gave us tools for a highly dynamic music system. We wrote a custom Wwise plug-in that allowed us to pack three stereo tracks into a six-channel file, which can be mixed at runtime. These tracks were composed ‘vertically’, so when a threat draws closer or becomes aware of the player, the music layering system can dial up the suspense.

Haydn Payne: During encounters with the alien we usually play one of our pieces of suspense music — mostly orchestral but with some synthesised/sound design elements. We fade each of three group layers up and down in real-time according to game events. For instance, if the player is hiding in a locker, the music will sound almost ambient with the alien in the distance, but as it approaches, the intensity of the music rises and the high strings will become loudest as the alien walks right past you.

If the music always responded directly to the alien’s proximity it could harm the game-play by giving away his position too easily, so throughout the game we change how we control the parameter that fades the levels up and down.

One of the alternatives is the music reflecting the degree to which the player is being stealthy by using code to calculate how close unaware hostile enemies are, increasing the tension level as the player sneaks close to them.

We can also script the music to change in different ways when the player sees particular objects or characters — say playing a sting when the alien walks round a corner into view, and subtly increasing the volume of the music as the player approaches a particular part of the environment.

A lot of this is controlled by the enemies’ AI state. As the alien charges to attack we usually trigger a short music riser which builds up to the point when the alien reaches the player. We also use the AI state of the hostile humans to control action music, which has three levels of intensity we switch between based on how aware the hostiles are and how much danger the player is in.

Bullock: We’re constantly asking ourselves, what should the player feel and how can we achieve that? For instance, layering subliminal non-literal sounds underneath real-world sounds to give them an emotional connection; like adding alien hisses into steam blasts and doors closing, or alien screeches into fire bursts and metal corridor groans. We did that sort of thing a lot. It helps to keep the player on edge. The player thinks they heard the alien — or did they?

Sound can be a great tool for misleading the player and at the same time it’s great for doing the opposite, leading the player. Sound can direct the player to a certain area or tell you what’s happening behind a door, like someone screaming in the next room. All these off-screen sounds can tell a story in their own little way and ultimately contribute to the greater narrative.

We even track your real-world sound, so if you scream on your sofa you’ll give away your position in-game!

RESPONSES