Cracking the Whip

The only way for Blur to make a new album was by pretending they weren’t. Without any pressure to perform, The Magic Whip’s template was cobbled together in a secret Hong Kong jam session. But it took a pair of Stephens, Street and Sedgwick, to whip them into shape.

Artist: Blur

Album: The Magic Whip

While band breakups can get messy, there’s also no easy script for getting back together. Besides being able to stand each other, the main challenge for reformed acts is to regain artistic credibility.

Most sidestep producing any significant new material. The money’s in the touring and reissues anyway, so why taint a perfectly good back catalogue. Especially one that’s aged beyond criticism. Blur had walked this well-trodden path ever since the band officially reformed at the end of 2008. Until recently, all the band had released since then were three singles. An attempt at recording more new material with producer William Orbit — who had produced their last effort as a four-piece, 13, and had a hand in the band’s last album before the final split, Think Thank — was aborted.

So when Blur announced their first studio album in 12 years, The Magic Whip, there was plenty of speculative buzz. Would this be down-in-the-trenches Parklife Blur, or another spinoff for Blur frontman Damon Albarn like Gorillaz, or worse, an opera? To heighten expectations, and perhaps waylaying any doubt of Albarn co-opting Blur as another side project, original guitarist Graham Coxon would be fully involved, having left after 13. Magic Whip also marked the return of producer Stephen Street, who played a central part in the making of the band’s classic mid-1990s albums, such as Modern Life Is Rubbish, Parklife, The Great Escape and Blur.

The collective self-doubt of being able to produce any decent new material together initiated an incognito act — secretive Hong Kong studio jam sessions that The Magic Whip was later cut from. During the Hong Kong sessions, Blur pretended — even to themselves — that they were not, in fact, recording a new album. In short, as per Douglas Adams’ instructions for flying — ‘The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss’ — Blur’s album-making strategy involved trying hard not to make a new album, and missing.

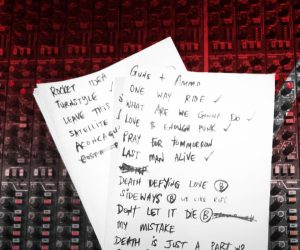

SECRET SESSIONS

Engineer and mixer Stephen Sedgwick was at the controls during the Hong Kong sessions, and also co-mixed The Magic Whip with Street. Sedgwick cut his teeth at the Pierce Rooms in London, where he came up under now famous names like Steve Fitzmaurice and Tom Elmhirst. At the end of 2004, Albarn came into The Pierce Rooms to work on the second Gorillaz album, Demon Days. Sedgwick stayed in touch with Albarn, and since 2006 has engineered and mixed most of Albarn’s projects at the musician’s private facility in West London, Studio 13.

Blur’s first accidental step towards making a new Blur album, recalled Sedgwick, was a few days of unscheduled free time. “In April 2013, while already on tour, the band got the news that their Tokyo gig was cancelled. As a result they had five or six days to spare, so they decided to go into a studio and make some music. I researched studios in Hong Kong, and Avon Studios seemed like the best option. I really like working at a large analogue console — we have a Neve VR72 at Studio 13. While Avon has a mix room with a Neve VR, I chose another studio with an SSL J-series, because it has a live room as well as a decent-sized control room. It made it possible for everyone to play together if they wanted.”

By the time Sedgwick flew out to Hong Kong in May, he still had no idea what the band aimed to do. “There really wasn’t an objective, other than them all being in Hong Kong and wanting to go into a studio to see what would happen. The band had come into Studio 13 a few times in previous years, in 2010 and 2012, to record three singles, and each time there was a clear brief and time schedule for them to finish those songs. But in Hong Kong there was no pressure on them to produce something finished. It was easier for them to be creative together and get ideas down.

“They just wanted to play together and record as many ideas as they could, without listening back, let alone editing, comping or creating finished structures. They wanted to keep the momentum going. I was recording into Pro Tools all the time. Damon had some sketches in his iPad they used as starting points. They would talk about them, then start playing and try different things to get something cool together. Rather than take stock at the end of working on one idea, they preferred to go straight onto something new. We were there for four days, and they worked on four song ideas a day, so we ended up with a lot of material. On average each song session was 30 to 90 minutes long.”

MARK OF SUCCESS

The band kept playing and playing, stretching Sedgwick to ensure everything went down properly. During the process, he managed to add a modicum of structure to the ballooning material. “There was a lot going on, and Damon could jump suddenly from one keyboard to another,” recalled Sedgwick. “It was quite hard making sure everything went down with good recording levels and that all the guys had good headphone balances. I always record everything when working with Damon knowing he may want to refer back to something he’s done earlier. I try to put markers in the sessions wherever I can. In this case, if the band had been recording an idea for 90 minutes but it only began to take shape in the last 40, I’d mark that in the Pro Tools session, either as a marker or in the comments boxes. Similarly if someone commented, ‘It sounded great 10 minutes ago.’

“That way whoever came back to the sessions would know how people had been feeling at the time. In the same vein, once the band settled in a groove I’d give them a click, which would also make it much easier to work with the material later on. While we rarely listened back to what we did, they very occasionally did a few overdubs. Graham might have two ideas for a section, and overdub a guitar part on the last few minutes. And Damon sometimes added extra keyboards. But we never stopped to listen back and edit. It was all about keeping the ball rolling. While they played, Damon would add some guide vocals with melody ideas. Many of the songs were being recorded as they were being written.”

CONTROL SAMPLES

In terms of the recording setup, two major adjustments were quickly made before the band settled into the session. “Before we went to the studio they had talked about wanting to play together in the live room,” recalled Sedgwick. “Which is why I had selected that SSL studio. But when we arrived, the band decided they wanted to be in the control room. There wasn’t a lot of space there, but enough for Damon with all his synthesisers, and for Alex [James, bassist] and Graham. Dave [Rowntree] set up his drums in the live room, and I had them all mic’ed up. But once they started to knock around ideas, Dave felt a bit isolated out there, and wanted to be in the control room too. So he grabbed a kick, snare, and hi-hat that were lying in the studio, set them up on the side of the desk, and started playing along with the band from there. Everyone being in the same room was a lot more vibey for the band.

“Of course having Dave in the control room made recording more difficult, but at that stage we were just thinking of getting ideas together, and not aiming for final drum takes. So I just put one Beyerdynamic M160 ribbon up as an overhead, and then a Shure SM91 inside the kick drum, expecting that all the drums would be redone at a later date. But it turned out that maybe half of those drum recordings made it to the final album, with additional drums and percussion layered later on. Dave did play his live room kit on a couple of songs, for example the big drums in Thought I Was a Spaceman. I recorded those with a Shure SM91 inside the kick and an NS10 woofer just outside it, Shure SM57s for the snare top and bottom, the hats had a Mercenary Audio KM69, and Sennheiser MD421s on toms.

“Damon’s vocal mic was a Neumann KMS105, which is super-cardioid, so it didn’t really pick up much spill from the drums, and Graham’s vocal mic was a Beyerdynamic M88 dynamic, which is also good with spill. Graham’s guitar amp was in the hallway, so we didn’t have the sound in the room, as it’s very loud, and I recorded that with a ribbon and a dynamic, in this case a Coles 4038 and another M88. I also recorded Graham and Damon’s acoustic guitars with the M88, which is a bit posher and brighter than a Shure SM57 or SM58, and Damon played some upright piano, on which I had two Neumann KM84 mics. All mics went through the desk, for simplicity. Alex’s bass was DI’d into the desk, as were Damon’s keyboards, which consisted of a Moog Little Phatty, a Teenage Engineering OP1, a Korg MS10, a Critter & Guitari Pocket Piano, his iPad, an Omnichord, and an old Russian synth called a Maestro. You can find information on it on ruskeys.net, a database of Soviet-era synths. It wasn’t easy to import Western synths into the Soviet Union, so they were making their own. They have a really aggressive, cold sound you don’t get from other synths.”

Despite still being unsure of the outcome of their brief stay at Avon Studios, Sedgwick wasn’t taking any chances. Before the return flight to the UK he copied the material over three different hard drives, which were each transported back via different means. Still, that could easily have been the end of the entire story. It wasn’t until over a year later that Coxon expressed an interest in revisiting the material. His idea was to do this with producer Stephen Street, with whom he had worked on several of his solo albums. Albarn gave the green light, and so in the autumn of 2014 Street and Coxon set about what at first sight appeared to be a mammoth task.

Blur’s album-making strategy involved trying hard not to make a new album, and missing

PAST A BLUR

From his studio in South London, The Bunker, Street recalls, “When Graham first contacted me I was delighted to be asked and involved in what could potentially become a new Blur album. But the band and their management were very keen on us keeping it as quiet as possible, because at this stage we’d still only been given the go-ahead to explore and work with the material, and there was no commitment to create a final album. As a first step I told Graham I wanted a week to simply immerse myself in the material without anyone saying, ‘listen to this.’ I wanted to be completely uninfluenced by other people’s opinions, sit through everything and get up to speed. Also, I had not worked with Blur since 1996, and wanted to get back into the Blur world again.

“Graham agreed and told me I had carte blanche to cut together whatever I felt was right. So I did a ‘Save As’ for each session, and laid the main instruments out in stereo pairs on my 16-channel Audient Zen desk, and started listening. Once I knew what was there, I started moving things around in the Pro Tools session. Some songs were more formed than others. There were songs that had a bit of vocal, then nothing, then some more vocal much later on. Sometimes Damon was singing ideas off the top of his head. A couple of the songs Damon had worked on after they had come back from Hong Kong — Ghost Ship and My Terracotta Heart — had a bit more shape to them, but were still slightly rambling without intros or outros. Other sessions had no vocals and no clear shape whatsoever. But basically I listened to all the ideas and started putting some shape into them.

“After Graham came back a week later, we spent another four weeks together working side-by-side on what was there. Obviously we started on the songs I’d already edited into a bit more shape, and then he pointed me to things that were not immediately obvious. For example, the sessions for Thought I Was A Spaceman and There Are Too Many Of Us appeared at first to be just them jamming around on a chord sequence without Damon singing, so I was a little lost. But at the start of these sessions he showed me Damon’s iPad Garageband demos, and suddenly they made more sense. Damon also had some nice key elements, like electronic percussion, in his demos.

“Graham and I were not only selecting the best sections and creating song structures, but also playing around with the arrangements. For example, in the song New World Towers — originally titled Trellick Towers after a well-known 1970s West London high-rise flat close to where Damon lives — Graham plays this descending guitar line, and I wanted it to build a bit more before it went into that, so I worked in some repeats there. We also truncated and chopped up Alex’s bass in that song to be slightly spacious and dubby, a bit like on his solo material. I found a place elsewhere in the session where he was playing more freely, and it worked better with the guitar parts. Graham and I were like kids in a toy shop: ‘let’s try this, let’s try that!’

“Graham would also overdub new guitar parts, and on Pyongyang, because there was no melody on the chorus, Graham wrote one, which is still there in the final chorus of the song. It turned out Damon actually had a melody for that part, which is fantastic, but I was keen to keep Graham’s melody too. In the last chords of the song you can hear the two vocals going in and out with each other.

“I thought Lonesome Street sounded a bit lethargic. It was recorded at the same 101bpm tempo as Damon’s iPad demo. To see how the song would sound sped up, I sampled everything into four and two bar sections, applied Elastic Audio, and raised the tempo to 110bpm or thereabouts. Those were the things we had to come to grips with, cleaning things up and arranging them to the point where they sounded as close as possible to being releasable.”

STREET’S BUS LANES

Street explains that in his attempt to make the songs sound as ‘releasable’ as possible, he continuously worked towards a final mix, which meant applying plug-ins and outboard as required, “trying to make it sound like a finished record, rather than a jam session that had been cut up. The outboard I used would mostly have been compression and EQ on the stereo pairs I had for the drums, guitars, vocals, keyboards, and bass bus. At my studio I used my Thermionic Culture Phoenix valve compressor on the drums, a dbx 160X on the bass, sometimes I had the Culture Vulture on the bass, and I had an old TLA EQ across the guitars and sometimes API EQs.

“When Graham and I had taken the songs as far as we could, we took them to 13, to play them to Damon. Stephen [Sedgwick] was also there. Damon was like, ‘great, fantastic! You want me to finish it off now, record the vocals, and then do a final mix?’ I told him I wanted to see it through to the end product and work with him on recording the vocals, and Damon agreed. I felt we needed to get Dave back in to play some new drum parts, Alex to play some more bass, and Graham to finish his guitar parts. Our next stop was Assault & Battery Studio 2, where I spent a couple of days with Dave doing new drum overdubs. Alex, Graham and myself then also added final overdubs, for the most part at my studio.

“So contrary to some reports that everything on the album emanated from the Hong Kong sessions, we did fresh overdubs on pretty much everything. If you cut and paste everything too much it sounds like it’s put together artificially. This album is obviously very much a product of its time, insofar as manipulating and editing audio that is on a hard drive is concerned. To do it with tape would have been a nightmare. The facility to edit and pick the nitty-gritty, best bits of those initial sessions is a key thing. Pro Tools is fantastic, it allowed us to keep a lot of the vibe the band had in the studio in Hong Kong. But you do need people playing loosely over the top to free things up, so that’s what they did in London.”

Sedgwick: “Studio 13’s EMT 240 plate supplied most of the reverb you can hear on the vocals. I used the Distressor again on the vocals during the final mix. During recording I have it on the opto setting, doing very little, and during mixing I have it on a 3:1 or 4:1 setting to hold the vocal in place. On the guitar bus I had two Chandler Germanium compressors, and I also had a spring reverb called the Welter Rev 5 on some of the guitars, as well as on some of the synths. I had the Retro Instruments 2A3 on the drums, which is a Pultec-style EQ, and also the API 2500 and on some songs the Chandler Zener limiter. I had the Urei Blackface 1176 on the bass and on some songs the Tube Tech EQ for some added weight.

“On the mix bus for the entire record we had the Cranesong Ibis EQ, then an Alan Smart C2 compressor, and finally the Manley Vari-Mu. The Smart added punch and the Manley ties things together in a really nice way.”

STOPOVER TACTICS

Sedgwick also recalls the moment the project finally moved on to the next stage; to try make a good album, and not miss: “What Graham and Stephen played to Damon and I sounded fantastic. It was so close to being the record! But there were only bits of guide vocal and it obviously missed proper vocal takes. It was at that point Damon knew there was going to be a new Blur record. That would have been in the late autumn of 2014. After this, Stephen [Street] went out and added more overdubs with the guys, and we also did a string session at Studio 13.

“The lead melodies were already there, whether they were Damon’s guide vocals on the actual Hong Kong recordings or whether he had them in his head, but Damon still needed to write the lyrics. Before Christmas he went back to Hong Kong to get inspired for the lyrics again! He’d been touring with a band for his solo project, Everyday Robots, in Asia and Australia, and at some stage he passed through Hong Kong. He had 24 hours there to immerse himself in the city again, get back into the same mood he was in when we recorded there and gather ideas for what he was going to write for the album. He retraced his steps from the hotel to the studio, and just hung out there to get his head back into that world. He wrote all the lyrics back in the UK, and in January, Stephen [Street], Damon and I went into Studio 13 to record the final vocals and overdub other bits and pieces.

“When recording vocals at Studio 13, Damon always likes to record in the control room. I was using the studio’s Flea 47 microphone, which is obviously based on a Neumann U47, and has a really warm and present sound. That went into an Audio Maintenance AML ez1073 preamp, and then a Distressor to help set a good level into Pro Tools. On a couple of songs he used a hand-held Neumann KMS105 microphone for a louder vocal performance. Graham also did some vocals and backing vocals, and on him I used a Neumann U77, again going into an Audio Maintenance 1073. He also did some more guitar overdubs, playing via the studio’s Vox AC30, on which I had a Coles 4038 ribbon and an SM57 or M88 dynamic. He may also have overdubbed one acoustic guitar, with me using the U77 on that as well. Damon also overdubbed some more synths, and a piano and an acoustic guitar. On the strings I used two Coles 4040 mics as a stereo pair, through AML ez1073 mic pres, and the close mics were Neumann KM84s on the violins and AKG C414s on the viola and the cello, going through the Neve board mic pres.”

The lead vocals in There Are Too Many of Us, has distortion and reverb inspired by Damon’s iPad demo

STEREO STEPHEN MIX

With The Magic Whip closing in on lift-off and the vocal recordings and final overdubbing completed, the two Stephens joined forces for the final mix at Studio 13 over two and a half weeks. Street explains, “By the time I got back to Damon’s place in January for the final recordings, Stephen had already been playing around with the tracks to get them to sound the same as they had sounded in The Bunker. But because he has more faders on his Neve V76, he could split some things out over more channels, like spread the guitars out over six or eight.

“Our starting point was the rough mixes from The Bunker, and then we refined that. Every time we overdubbed we were saving rough mixes in the computer and on the desk, and bit by bit we got closer and closer to that final balance. By the time we had recorded the vocals at Studio 13, we had gotten pretty close to the final result. For each song we had every mix from The Bunker and every Studio 13 rough mix on two external drives, and every once in a while we would refer back to those to make sure we weren’t losing our way. Sometimes you get those instinctive balances in rough mixes that are integral to the song.

That Sedgwick and Street share first names, and initials, is a curious and irrelevant coincidence, but Street pointed out a more significant similarity. Despite being a generation apart, the two Stephens very much have the same working methods in the studio; both like working outside of the box, with a hybrid plug-in/outboard approach.

Street commented, “Stephen is very meticulous, and when he saw us working side-by-side, Damon joked he could see why he picked Stephen to work with, after having worked with me for much of the ’90s! It was a joy to work with Stephen, having worked by myself in recent years. It was like working with Cenzo Townshend and John Smith in the nineties. Stephen would start work in the morning on a mix, and after a couple of hours I’d come in fresh, and I’d have a few comments and would make some changes. Together we’d hone it a bit more and fine-tune the sound on the drums or the bass, things like that.”

Sedgwick: “I have always worked on analogue desks, and the Neve VR is just a great desk to mix on. I like the physicality of reaching for faders and not having to look at a computer while I judge what’s coming out of the speakers. But I now like to use the best of both worlds. Some plug-ins sound great now, and the computer is great for the recall side of things, especially during writing and tracking, when you can call up what you did before with all the plug-ins and levels there. With this project, what Stephen and Graham had pieced together in The Bunker already sounded pretty mixed. So it made sense to carry on from where they left off at 13. That’s why during the final mixes a lot more of the tracks remained submixed in Pro Tools than normal. Stephen brings things out in stereo pairs, puts outboard across those, and places plug-ins on individual tracks in Pro Tools. I continued with that working method, which meant that mixing was very fast. Some mixes only took four hours and in some cases we did two mixes a day.”

Street: “When Stephen opened the sessions he initially kept any plug-ins I’d used at The Bunker, and if 13 didn’t have them, he purchased them so we could carry on from the mixes I’d developed already. I’m a big fan of the Universal Audio plug-ins. I think they’re really good, and have invested quite a bit in them. I use the Lexicon 224 and EMT reverbs, and recently bought the Ocean Way room reverb. I used it on the drums in Go Out, and printed it as a reference point. I also love the Waves Kramer Pie compressor, which I often use on vocals, and SoundToys’ EchoBoy is my go-to delay. The Samsamp is nice if you want things to sound a bit distorted. Sometimes using plug-ins is just convenience; you call it up and it’s there. But when it comes to key elements in the track like the drums, bass line compression, and vocals, I often still put it through some outboard as groups. Steve is exactly the same. So that is exactly what we were doing at 13.”

DISPLACED ATMOSPHERE

One of the most notable things about The Magic Whip is how much the band and the two Stephen’s work with atmospheric sounds, including reverb, delays and distortion, particularly on the vocals, somehow managing to emphasise the urban nature of the music, and the sense of alienation and displacement that permeates many of the lyrics. Sedgwick explains, “The weird synth parts are mostly from Hong Kong, picked up by Stephen. But most of the effects, like reverbs and delays, were added by us later. The street sounds come from both Hong Kong and London and were mostly recorded by Damon on his iPad, which he always carries with him. Actually, the very opening sound of the album is a piece of firework called Magic Whip, which Damon set off and recorded on his iPad. I think he did it in Iceland.”

Street: “The lead vocals in the song There Are Too Many Of Us, has distortion and reverb inspired by Damon’s iPad demo. He’d demoed that song in Garageband, singing straight into the iPad mic and added tons of distortion, which made his voice sound very otherworldly. I was keen for his final vocal to sound similar. Damon has a wonderful voice which sounds great when it’s recorded straight, but on this album we really wanted to put his voice in certain spaces, to make sure it carried the atmosphere of travelling and feeling disconnected. I’m really pleased with the changes in vocal tone throughout the record.”

Sedgwick: “Some of the effects were achieved using plug-ins, and some in the outboard I had on the stereo groups. Our general outboard mix setup did not change much from song to song. Studio 13’s EMT 240 plate supplied most of the reverb you can hear on the vocals. I used the Distressor again on the vocals during the final mix. During recording I have it on the opto setting, doing very little, and during mixing I have it on a 3:1 or 4:1 setting to hold the vocal in place. On the guitar bus I had two Chandler Germanium compressors, and I also had a spring reverb called the Welter Rev 5 on some of the guitars, as well as on some of the synths. I had the Retro Instruments 2A3 on the drums, which is a Pultec-style EQ, and also the API 2500 and on some songs the Chandler Zener limiter. I had the Urei Blackface 1176 on the bass and on some songs the Tube Tech EQ for some added weight.

“On the mix bus for the entire record we had the Cranesong Ibis EQ, then an Alan Smart C2 compressor, and finally the Manley Vari-Mu. The Smart added punch and the Manley ties things together in a really nice way. We printed all the mixes to ½-inch tape, at 30ips, because tape adds something you cannot get any other way. As a reference we also sent digital mixes through the UAD ATR102 Master Tape Machine plug-in, and this also sounded great and definitely added something to the mix. But when we printed straight from the desk to the Studer, the tape machine won out almost every time. The bottom end just sounded fantastic, really tight and warm.”

The Magic Whip went to number one in the UK, and has been Blur’s highest charting album in quite a few countries, including Australia and the US. The reactions from the critics have also always been overwhelmingly positive, suggesting that Blur, with help from the two Stephens, has managed to whip up something more than a magic blip. Undoubtedly the band’s paradoxical strategy of trying hard not to make the album, yet miss, added its own whiff of magic, with the two Stephens in particular responsible for getting the project to fly.

RESPONSES