Cooked Raw: Welcome to 1979

We follow Welcome to 1979’s Chris Mara through the edge of your seat process of direct-to-disc recording and find out what it truly takes to ‘cut’ a record.

There’s an ingredient lacking in the Raw Food movement — immediacy. If I’m going to eat uncooked superfood spheres followed by a serve of matcha hemp chia pudding, I bloody want it now!

You know what good raw food is? Grabbing a carrot out of the fridge and chomping on it like Bugs Bunny. That’s ‘what’s up’ — raw, untouched, pure unadulterated carrot, direct to my mouth without mashing it into some tasteless tahini-tempered puree.

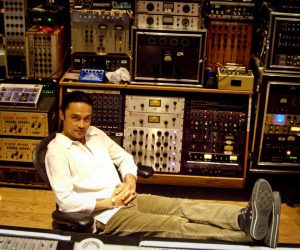

Chris Mara thrives on immediacy. He’s built a business out of it; well, several business actually. There’s his studio, Welcome To 1979, a purely tape-based Nashville studio he built eight years ago to keep track counts low and sonic austerity at a high. Though, he admits, the decision to not secure a Pro Tools rig at the time was as much about business as sonics. “I had a financial choice to make,” reasoned Mara. “Getting a 24 I/O Pro Tools rig was about $40,000. The place I wanted to rent was about 8000 square feet. I already had a two-inch 24-track, my console and a bunch of outboard gear. Why spend 40 grand to be just like everybody else and then have that payment? I could not get Pro Tools, and that would be my thing.”

Welcome to 1979 drew notoriety for its ‘hard line’ stance, and other engineers started calling up to ask where Mara had his machine restored. “I restored it,” he’d explain to them, which spawned another cottage business, Mara Machines, which can supply any flavour of completely restored MCI tape machine — from a ¼-inch two-track to a two-inch 24-track — for an affordable price. “In the first year we did one every other month and it helped fund the studio because it was extra money. Every year it’s been doubling. They go everywhere — Greece, Mexico, Canada, Vietnam — last year we did 50. We’re by far the largest tape machine restoration company in the world. I’ve got a warehouse with about 40 of them in there right now. I bought two today and two on Monday.”

Eventually, Mara relented and installed a Pro Tools rig in the studio because “we do so many transfers and I do a lot of mixing in the box. We track to tape, the band goes on the road, I transfer it to Pro Tools and send them mixes.”

Having a digital rig also provides a playback solution for his most immediate recording solution; direct-to-disc recording.

CUTTING, A NEW HIGH WAY

Literally ‘cutting records’ from a lacquer as the artist is performing live is as much science as art. Welcome to 1979 only got into cutting its own lacquer masters about three years ago. Because many of Mara’s clients came to him specifically to record on tape, they were also more likely the type to take that next step down nostalgia highway and press vinyl. “I started sending a lot of projects off for other people to press and some sounded really good while others sounded really bad,” said Mara. “I wasn’t sure why because I didn’t know anything. So I called a mastering engineer to ask what was going on. He said I should get into cutting my own masters and offered to teach me how. I bought a lathe, had it restored and almost immediately started cutting a lot of records.”

But it didn’t stop there. Mara: “The guy that restored it for us said ‘You’ve got to cut direct to this sometime, since you have a studio connected to a lathe, and they’re in the same building. That never happens.’ Usually the lathes are in mastering studios and there’s no way you could physically do it.”

So over the last year, Mara has started cutting the odd project directly to a master lacquer, the sixth and most recent was Josh Hoyer & The Soul Colossal’s Cooked Raw — fittingly, the record has six tracks from the six-piece band.

Hoyer and his ensemble tour hard — they’ve put 75,000 miles on their van in the last two years — and a lot of their fans appreciate the raw, uncooked live version. “They tell us they love our studio albums but it doesn’t capture what we do live, which is where we sound the best and our energy is. After all, that’s what soul music is supposed to do, connect with people,” said Hoyer. “So I said, ‘Let’s just give this a shot, go direct-to-disc, and capture that energy.’”

There were obviously things that were out of the question: backup vocals, certain layering techniques… “But I like how it came out,” said Hoyer, who enjoyed the process. “It is what it is, like the jazz recordings I’ve listened to for so long. There were definitely lots of upsides. We took some chances. The leads — whether, trombone, sax, guitar or whatever — can play off of each other better. You’ve got that immediacy and interplay that helps bring the groove together. You capture much more energy than when you’re just playing one instrument at a time. We were all able to watch each other. I mean, it’s like playing a show. We’re probably going to do another one down the line.”

While there wasn’t room for any overdubs, it didn’t stop Mara and Hoyer getting a little inventive with the setup. Hoyer usually plays a combo keyboard, switching between B3 and Wurly patches on the fly. The day before the session, the keyboard got dropped after a gig… perfect timing. Luckily Welcome to 1979 has a healthy collection of vintage instruments, including both a Hammond B3 and Wurly in great condition. “We ended up putting the B3 in his vocal booth with the Wurly off to his left,” explained Mara. “It was the last thing we discovered. I had to put up two vocal mics (one over each keyboard), but I didn’t have a matching pair. So I set up a Neumann U47 and Miktek CV4, EQ’d them to sound the same, and bussed them to the same compressors — an Avalon 737 with a dbx 160 set up behind it acting more as a limiter.” For the whole session Mara watched Hoyer like a hawk, switching faders as he jumped between the two mics. “He would do it mid-sentence!” exclaimed Mara, forcing him to participate in the session as ardently as the band. “He was kind of in the room playing along with us,” said Hoyer.

Along with Hoyer’s double keyboard and vocal combo, the Soul Colossal has a drummer, bassist and guitarist, and two horn players. Mara put the rhythm section in the live room, taking a direct line from the bass and combining it with the amp signal. The guitarist’s amp was isolated, as were Hoyer’s B3 and Wurly amplifiers. The studio also has a large entryway between the live room and vocal booth, with windows looking into each. It was a perfect position for the horn players and meant everyone could see each other.

Once the setup is locked in, the band will record one side at a time. They’ll go in, perform a four song set leaving a couple of seconds between each song, then cut another four songs for the other side. Mara reckons four is a good balance between getting the most out of a side while limiting howlers. In this case, it was three a side. The song order is just down to common sense; what feels right, and eliminating any unnecessary changeovers like capos and tunings that mean you’ll be swapping guitars every song. Having one guitar player also cuts down on tuning issues over four songs.

It’s sonically one of the best ways you can record because it’s literally microphone, console, lathe — you hit a note and it’s on the master lacquer in a fraction of a second

CUTTING HIS TEETH

Mara wasn’t coming to the process cold. Over the years, he’s done a dozen or so live to ¼-inch two-track records for the Upstairs at United project. In a room above the United Record Plant, Mara would cart in an all-analogue setup of a 16-channel console, some outboard, and mics to capture performances live to tape. The lineup of musicians was diverse, from Jack White-offsider Brendan Benson to American indie band Cults, British piano rockers Keane and Australia’s urban cowboy, Henry Wagons. It was great practise before taking the next step towards tracking direct-to-disc, which adds a level of live complexity at the cutting head.

For a quick education Mara and mastering/cutting engineer Cameron Henry turned to mastering engineer Hank Williams for a masterclass on how to operate the lathe. “He turned us into experts in a short amount of time,” said Mara. “Because he’s so knowledgeable.”

AT: What are the limitations of the medium?

CM: “We can pretty much put anything on it. Because it’s a physical medium, it has physical limitations — mainly on time and volume. The louder the record the shorter it is and vice versa. You want a record to be loud because vinyl records have a noise floor and you want to be above that as much as possible.

“Playing back is where the issue always is. The stylus is going left and right for mono and up and down for stereo. It’s moving around, and we have to rein it in enough so the music and energy doesn’t change but everyone can play it back on their turntable.

“On a typical cut, you’d send us your music and we would audition it; listen to it, often do a test cut and listen to that, then do a master cut. This is all on the fly. We play it a little bit safer than normal because we don’t want to capture a perfect performance then find out it doesn’t play back on a turntable because the kick drum’s too loud. That said, you take a master to the plant and there’s two more processes that need to take place. They could still totally screw the pooch on it.’

AT: Sounds like you need a few hands just to make it work.

CM: “On a direct-to-disc session it gets pretty complicated because I’m mixing in the control room with my assistant, and Cameron’s in his mastering suite with his mastering assistant. Our assistants are on the phone to each other, because you don’t just say, ‘Rolling’. He has to drop the thing down and wait for the lead in, then say ‘Go’ before I can tell the band to play. It’s not instantaneous, and he could have a problem that forces us to stop. There’s a lot of choreography there, but it’s pretty fun.”

AT: Once everyone’s rolling, what happens next?

CM: “Cameron’s highly skilled. When you tell guys that cut a lot of records that we do direct-to-disc, they kind of go, ‘Damn!’ On a standard cut one of the main things our lathe and models like it can do, is change the distance between the grooves based on how loud the music gets. It means you don’t waste space on the record, and can have a louder record.

“On a direct-to-disc you can’t use that system, because it’s live. Cameron is listening, watching and changing the spacing manually. If it gets quiet, he’s looking at the microscope to see how close the grooves are and as it gets louder he starts to wind it out so we can still have a good, loud record. It’s called ‘packing the grooves in tight’. It’s pretty impressive to see one under the microscope that’s done really well.”

PRO TOOLS PAYS OFF

While there aren’t any edits done to the performance, the band does get multiple shots at recording a side. But when it comes time to choose which performance was best, there’s a problem: You can’t listen back to the master lacquer because it will degrade it.

Getting around that issue has a two-part solution. Right at the beginning of the session, the band records a reference lacquer and listens back to it. This isn’t one of the final takes, so it’s okay to play it back. If everything sounds good to them, they sign off on it, and recording proper gets underway.

During the final performances, the outputs on the lathe are run into the Pro Tools rig, though Mara is quick to stress, that there’s nothing between the console and lathe. A duplicate of what’s gone down is recorded into Pro Tools so the band can listen through all their six takes and decide which is best without messing up the lacquer. “It’s fun to watch bands listen to them,” said Mara. “Because they’re not just listening to their part. They’re listening to the whole thing. It’s about weighing up the mistakes against the energy.”

SKILLS TO TURN THE WHEEL

From a recording engineer’s standpoint, Mara likes the idea of challenging himself and his skill sets with more analogue productions. “I’m not trying to demean anyone with Pro Tools skill sets,” said Mara. “I have them too. But it really is a challenge to do things direct-to-disc. Not many engineers today have ever done it.”

During the performance Mara would “ride guitar solos and the occasional snare fill. If it got to a down section on drums I would bring the drum room mics up a little bit to fill some space. They have such good dynamics that they kind of mix themselves. Even an overall static mix had a lot of dynamics in it. I would also grab more reverb in the keyboard and guitar solos as well.

“I won’t mute at all, because it really pulls the air out. In a typical mix, it’s cool, but in this scenario all the ambience disappears. Initially I was muting and unmuting his two vocals mics, but it sounded too obvious, so I faded them instead. And at the end of the side I’m doing a fade.”

At the end of the chain, Mara has a stereo compressor and a limiter, just to round it off a bit. Henry also has a compressor and limiter in the lathe room, with a multi-band EQ so he can shape the signal. “I don’t have to think much about it,” said Mara. “I can just make a good sounding mix and rein it in a little bit. We don’t want to squeeze it because the more dynamic it is, the louder the vinyl record will be.

“If you sent me a torpedo, the record will be quiet because it can’t spread the grooves out and slam them in. They’re all just spaced the same. We try to keep the dynamic range but squeeze it a little because we’re not sure who’s going to jump in. Hoyer’s got horns and he’s very dynamic vocally, so it’s a mixture of leaving it alone, then if it starts running away we have processors that will clamp it down.”

MAKING THE CUT

So why go through all the pain of cutting a record directly to lacquer? Mara reckons there’s nothing quite like it. And he’s right. Mara: “It’s the trifecta. It’s sonically one of the best ways you can record because it’s literally microphone, console, lathe — you hit a note and it’s on the master lacquer in a fraction of a second. It’s fast because you come in for a weekend, or three or four days, and your record is done — it’s tracked, there’s no mixing, no overdub, no mastering, nothing. And it’s affordable because when you walk out of the studio, you have your master and you’re already one-third of the way into vinyl production. Rarely are things fast, inexpensive and good.

“Another nice thing is that no one’s doing it. It has a story built in, which you kind of need these days to stand out. People are over, ‘Hey, I recorded in a cabin in the woods.’ Or, ‘I recorded at home with a laptop.’ Everybody’s f**king doing that.”

Mara’s adamant that any act that plays their instruments could handle the pressure. After all, he says, “It’s basically like playing a four-song set twice, which bands do all the time. They go out and play four songs in a row without major screw-ups. It’s not impossible.”

RESPONSES