Steal Yourself: Recording Nothing But Thieves

An old MCI console arcing. Risible control room acoustics. An irredeemably bad drum room… Nothing But Thieves’ ’70s-style country manor residential studio fantasies proved hard to realise.

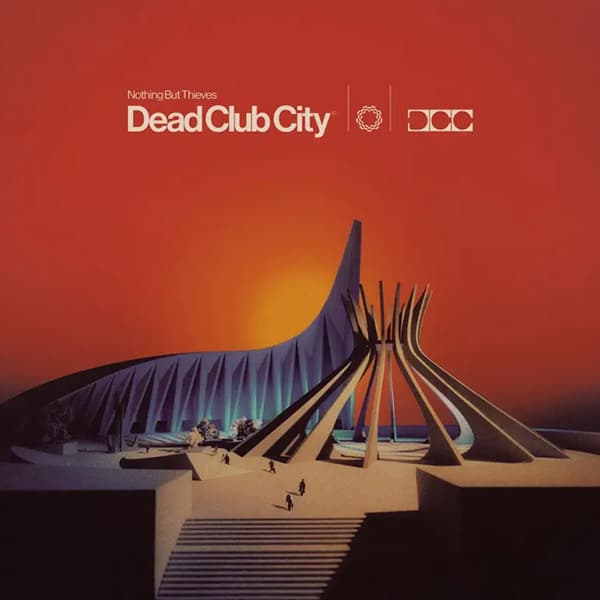

Artist: Nothing But Thieves

Album: Dead Club City

It’s been more than half a century since The Rolling Stones recognised the attraction of recording ‘in the wild’, rather than in the stifling confines of a recording studio. They created the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio for this purpose, and their legendary early ’70s albums Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street were largely recorded at Mick Jagger’s Stargroves manor house, an hour south of London. Countless bands followed suit, most famously Led Zeppelin, who recorded several albums at Headley Grange, also using the Stones’ Mobile studio.

As recording equipment became more and more portable and reliable, recording on location became commonplace. So when Nothing But Thieves decided in the summer of 2022 to record their fourth album in a country setting, they were travelling a well-trodden path. Their reasons were the same as those of countless bands down the ages: a hope that a comfortable, remote, non-studio location would lead to a great vibe, increased focus, heightened creativity and better results.

However, in the case of Nothing But Thieves’ fourth album, this strategy proved easier said than done. The English band did experience all said benefits from recording in the countryside, and the resulting album, Dead Club City, proved a big critical and commercial success (it was the band’s first UK No.1). But the path to getting there was distinctly and rather unexpectedly rocky.

ESSEX ESSENCE

Formed in Essex in south-eastern England in 2012, Nothing But Thieves broke through with their self-titled debut album in 2015. It was recorded at Angelic Studios just outside of Oxford, and mostly produced by Julian Emery. Broken Machine followed in 2017, produced by Mike Crossey, and Moral Panic in 2020, produced by Crossey and Dominic Craik. Both albums were mostly recorded at Crossey’s place in California, with Jonathan Gilmore working as an engineer on Broken Machine.

Dead Club City was released in June of this year, and co-produced by Dominic ‘Dom’ Craik and Jonathan Gilmore. The former is one of the band’s guitarists and main writers, and also responsible for synths and programming. The latter is a producer and mixer with credits that include The 1975, Rina Sawayama, Carly Rae Jepson, Beabadoobee, Lewis Capaldi, and more.

Via Zoom from their respective studios in London, Craik and Gilmore relayed how going off the beaten track in their case meant encountering many large-sized rocks, and how they circumvented or climbed them. Gilmore set the scene…

“I began my career working for Mike Crossey from 2011 to 2017. We did the whole of Broken Machine in five weeks, running two studios, with Mike in one studio, and Dom and I working in the other. Mike might be cutting the drums and bass in his room, while Dom and I would record the guitars and add programming before it went back to Mike for the vocals, and finally mix. It was a really tight schedule and thus a bit of a baptism of fire for Dom and I. We’ve been in touch since.

“During the pandemic the two of us co-produced the Nothing But Thieves song ‘Life’s Coming in Slow’ for the Gran Tourismo 7 video game. The sessions were a bit of a circus: Dom was at home with covid and we had to get from initial phone call about the project to finished master in about five days. Audiomovers and FaceTime saved the day! But it turned out well, and I suggested to Dom that we produce the entire next band album together in a similar manner (minus respiratory diseases). I really wanted to support the band in exploring the edges of its stylistic comfort zone.”

I’ve made a lot of records in a lot of different places and these were substantially the most adverse conditions under which I’ve made an album.

COUNTRY HOUSE

After the band agreed for Craik and Gilmore to be at the helm for the making of its new album, the duo, says Gilmore, “pushed for making a record that’s as creative and elaborate as possible and even a bit indulgent. To be able to do that we needed quite a bit of time, so the idea was to find somewhere where we could set up camp and stay for a long period. Dom and I ended up frantically sending each other links to online listings of country houses. We were inspired by Led Zeppelin working at Headley Grange, and Radiohead recording most of OK Computer at a manor house called St Catherine’s Court.

“Unfortunately, because of the British rental market we got priced out of our luxury country house aspirations. Instead, we ended up stumbling across a place in Essex called Kyoto Recording Studio that was surrounded by a 22-acre farm. I think it had aspirations of being a luxury residential studio, but the studio was extremely basic on a technical level, with some very substantial shortcomings.

“However, the place was affordable for the length of time that we required, so one pre-production aspect of this record was figuring out the logistics of transforming it into something where we would not only be physically able to record the album, but where we also would not go mad. The estate had a country house, and a barn that had gradually been repurposed into a recording studio. But there wasn’t really much diligence paid with respect to the install.

“We had to basically rip out the whole control room, replaced a lot of the furniture, and re-jig everything. I spent two days testing everything in terms of signal flow, and a lot of the cabling was dysfunctional. We replaced the Pro Tools system, all the headphones had faults, as did the guitar lines, and the acoustic treatment was very basic and quite ineffectual. The control room felt like a mixing desk slapped into a conservatory.

“Speaking of which, the desk (an MCI) was a hazard. Honestly, it felt a little like a fire risk. As you can see in the YouTube videos, at one point it started making a rather angry electrical buzzing sound. It had been very poorly maintained, so even though we had it extensively serviced, it basically didn’t work. In the end we just used it for a couple of line returns.

“After the two weeks to sort out the studio, we had quite a slow first three weeks of actual sessions, because we were still hitting a lot of issues. The air conditioning caused electrical buzzing on the mics and we had hornets in the control room. It was pretty rough and ready! I’ve made a lot of records in a lot of different places and these were substantially the most adverse conditions under which I’ve made an album.”

3 YEAR GESTATION

Although the team managed to create a functioning recording environment, there were more problems to come, as we will see later. To illustrate both the challenges and the magic of the recordings at the studio, the band made a series of YouTube videos , which Gilmore referred to above.

In the end, the entire recording process took 130 days, from August 2022 until January 2023. However, this had been preceded by a three year-long writing and pre-production period. Dominic Craik elaborates on the album’s genesis, first by clarifying how he ended up in the co-production role.

“I started playing guitar when I was six, and come from a classical music background. I can read music, and have a traditional understanding of harmony and how chords fit together from analysing chorales and string quartets when I went to music school. I then applied my knowledge of the guitar and the music lessons to other instruments, and learned how you can create an arrangement, and get this kind of holistic overview of entire pieces of music. This led to me writing and producing.

“[Singer] Conor Mason and [guitarist] Joe Langridge-Brown, and I started writing a little over 10 years ago, but discovered that we just couldn’t write songs to save our lives. It took years and years just to get the basics. At the start you think that because you can play complicated pieces of music on an instrument, you’re going to be able to translate that into writing songs. But it’s just not the case. Song writing is a completely different art form. There are songwriters that can’t even play instruments!

“We just kept pushing and pushing, and eventually the songs came. For many bands now, if you’re also recording demos, there has to be someone who can work GarageBand, Logic, or Ableton, even if it’s just for basic recordings. My curiosity was sparked by Logic, and I became obsessed with trying to copy some of the sounds on my favourite records and implement them in our music. It became this weird jigsaw puzzle to put together. I also learned how to navigate a synth, but I’m more comfortable creating sounds than performing on them. I would rather write out MIDI and send it via USB or MIDI to a synth than play it, because I’m not that technically competent as a keyboardist.”

FLESHED OUT

Craik continues by going into detail about the band’s actual writing process. “In general, writing and recording are quite separate stages for us. We try to write over a long period of time because we find that it gives the most successful results. You gain perspective. The more songs you write, the more you can pick from, and the stronger the album is going to be. You can rewrite things, re-demo, change stuff, if you like a chorus lyric from one song but it’s not the right song you can put it on something else.

“Dead Club City was born out of the pandemic, when we were first able to get back together after all the lockdown stuff. It meant that we were all creatively rearing to go. We had a lot of gas in the tank. The beauty of working as a trio with Conor and Joe is that they come up with ideas that are never fully fleshed out, and this has two benefits. The first is that nobody gets too attached to their idea because they haven’t gone down the rabbit hole of fully exploring it. The second is that you get this amazing level of collaboration, with everyone hearing things slightly differently.

“We wrote most of the material for the new album in my studio. It’s always a bit of a free for all, and there’s no tried and tested method. The last thing we do normally is guitars, which is funny because you’ve got two guitarists in the writing room, or two and a half if you include Conor. Inspiration could come from a synth sound, or a drum loop. It’s never the same, and that’s what’s exciting and one of the reasons why our music is so diverse. Only one song on the album was written in the studio, ‘Do You Love Me Yet?” which is a collective favourite, and one of the more experimental songs on the record.”

The control room felt like a mixing desk slapped into a conservatory.

EXTENDED PALETTE

By the time Nothing But Thieves descended on the studio in Essex, upgraded to suit their needs, everyone brought their equipment, and Craik tons of song demos on Logic. “They were pretty fleshed out,” he says. “On this last record, they were probably the closest they’ve been to the final product. The arrangements were also more synth heavy than ever before. After working on Moral Panic, I started collecting synthesizers, I built my modular synths and have a UDO Super 6, a Roland Juno 6, a Moog Sub Phatty and many others.

“Synths offer a whole different palette of sounds. Guitars are incredible, but for this album, synths gave me a new and exciting realm of creation. It was amazing to pull up a hardware synth, program a sound and be like ‘that reminds me of Rush or Phil Collins,’ or something, and be able to pull that into our music. There definitely was a lot of inspiration of the music from the late seventies and early eighties, all that synth-and-band hybrid stuff. It was a case of getting our paints and paintbrushes in front of us, and see what comes together.

“I also used soft synths. I’ll take whatever sounds good. Jon and I did a lot of A and B-ing of synths versus soft synths, and for example the U-he Diva is an incredible plugin, really thick-sounding, loads of character, and it doesn’t sound plasticky or thin or any of that kind of plugin stuff. Sometimes the plugins would beat the analogue gear, and you don’t even know why. I like hardware synths because you operate them with your hands and they’re fun to be with, but sonically analogue doesn’t always win.”

JUMPIN’ JACK PATCH

Gilmore: “So Dom brought all his toys and his synthesizers, and I brought in my full recording studio complement of gear and microphones, and all the various drums and accoutrements you need. We installed a Neutrik Jack Patch system whereby we could easily interface between the synths, the guitar pedals, and the hardware outboard, including Dom’s Binson Echorec, Roger Mayer 456 Tape Emulation, Thermionic Culture Vulture, several old nineties effects units, and so on. I’m also a guitarist, and brought my custom pedal boards and a big crate of loose pedals. We probably ended up with about 100 pedals between us!”

Craik: “From the outset we wanted to have a very fluid, quick and spontaneous relationship between the outboard, guitar pedals and synths. If you don’t colour synths a little bit, they can feel a little bit cold and separate next to the guitars. You need to run them through a guitar pedal or an analogue effects unit or an amp, to add a bit of grit, and make it all fit together. In addition to the Jack Patch, we also had a Radial unit (EXTC Radial reamp box), which took care of impedance and level conversions, so we could use easily route synths, outboard and pedals to each other.”

Gilmore: “Between Dom and I we had a great collection of guitar amplifiers: a Fender Twin, a Fender Vibralux, a Mesa Boogie Mark 5, a Marshall Bluebreaker and also some weirder stuff, like a Silvertone 1485 and a Laney Klipp, which we used a lot. We mainly used an Ampeg SVT stack for bass. All the bass performances (and some of the guitars) ran through a guitar amp and a bass amp simultaneously, so we could have that kind of throaty upper voicing on the bass guitars if we needed it, and low end on the guitars if required. In addition to all the guitar amplifiers we would also use a DI, often with pedals.

“All these different layers were phase aligned at the source, so the phase was coherent. That allowed us to make stylistic choices with the guitar, including some really idiosyncratic ones, to give them a lot of personality. We cut all the lead vocals with a Neumann U67. The tonality of that microphone suits Conor’s voice really well. It gives it a bit of a midrange focus that I think is very helpful. It went into a Rupert Neve Designs Shelford Channel mic pre. We had a big rack of Neve 1073 preamps for everything else.”

DRUM SURRENDER

The company recorded all the above at the revamped Kyoto studio in Essex, but the issues with the studio proved insurmountable when it came to drum recording, for which decent acoustics are the most crucial.

Gilmore: “I would say that the tone of the rooms was the biggest challenge in making this album, and it meant that everybody had to be on headphones a fair amount during the entire process. We mostly used Shure SRH940s, and also Audio Technica M50s. The control room had a pretty substantial null at around 110Hz, where all the good stuff is, so monitoring sounded really strange. It was quite drastic.”

Craik: “For monitoring, we normally use the Unity Audio The Rocks, which are great, but you can have the world’s most expensive speakers, and in a terrible room it will still sound terrible. It was a bit of a nightmare. We’d gone to the studio with the intention of recording everything there, but the reality was that the acoustic treatments were purely for show. Once we got to recording drums, it turned out the sound was uncontrollable, with mad resonances.

“After trying the main live room and a smaller side room for a week, we decided to record the drums elsewhere, and went to a small east London studio called Baltic. It has a great, very controlled and punchy live room, apart from the fact that they put in an upright piano in the live room, which caused quite a bit of ringing. We added a lot of aggressive compression to the drums on this album, which of course pulls up all sorts of resonances, so we did a lot of work on dampening the room and the piano, like gaffa-taping windows, and leaning chairs against things and so on.”

LOGIC & TOOLS MAKE FRIENDS

Throughout the recording process, Craik used Logic and Gilmore Pro Tools, which led to a lot of sharing of files. The latter explained, “I think it’s fair to say that Logic is a very creative environment for music production, and Pro Tools has an accuracy when working with audio, which cannot be matched. So recording and editing audio was all done in Pro Tools. Meanwhile, Dom was throwing ideas around in Logic. Our Engineer Freddy [Williams] was also on a Pro Tools system.

“It was a bit chaotic, but it meant that there were always three things happening at the same time, and multiple songs would come together really quickly. Conor and I would be recording vocals, Freddy might be editing backing vocals, and Dom might be working on a synth arrangement for a song that we are going to cut vocals for in the afternoon. I think this album is sponsored by AirDrop! All three of us sat in a room together, and along with the rest of the band it was an open forum of coming with ideas. It was quite a fluid process, with the three of us throwing files around. And fortunately we had a huge whiteboard to keep us all on top of what we were doing.”

Throughout the 130-day process, the original Logic demos changed remarkably little. Gilmore: “Because the arrangements were mostly already great, and the songs themselves were already the strongest contenders, it was not like other projects that I work on where pretty much all the demos require structural and tempo/key changes. Our process was re-recording all the main band elements and then enhancing things or modifying things to make them better. We did add a lot of stuff but it was to support and enhance what was already there: backing vocals, additional melodies, ear candy, and so on. I think only ‘Tomorrow is Closed’ and ‘Welcome to the DCC’ went through substantial compositional changes.”

Craik: “Once Jon had finished and finessed the recordings of the vocals and the additional instruments, that stuff would come back over to me and I would do additional production and get a rough mix together in Logic. I built these rough mixes over quite a long period of time, and many eyes and ears went over them, questioning everything. We gradually developed a detailed idea of what we were shooting for and what we’d send to Mike Crossey, who would be doing the final mixes. Once we agreed on a rough mix, we’d send it to the label, to management, to ourselves. Once it was approved, there was this massive transfer of my rough mix over to Pro Tools, and Freddy and Jon would spend days putting on the final touches.”

Gilmore: “The rough mixes reflected where the songs needed to go creatively, and then I would go through everything on a technical level, to make sure that everything we sent to Mike was as bullet-proof as possible, and we squeezed every last percentage out of what we had, with the absolute best drum sound we could get, the best guitar sound we could get, exactly the right vocal, and so on. The rough mixes were mostly delivered with compression and EQ on the tracks and everything else production-wise printed, because the sounds we wanted were all there. The exception would be the vocals which we did deliver with FX prints and live processing on the channel but without any processing committed to the audio. By that point we had usually been through multiple stages of rough mixing, so the production was really the way we wanted it.”

Gilmore might have added that they also made sure the material explored “the edges of the band’s stylistic comfort zone,” while still sounding like Nothing But Thieves. Despite, or perhaps because of, the adverse conditions, it’s exactly how Dead Club City turned out. As one critic put it, “It is distinctly Nothing But Thieves, but with a fresher, funkier twist and a concept album foundation.”

RESPONSES