Junior Wells, Brian Kramer & the Bluesmasters

Learning to be a record producer is not something you pick up from a text book; it’s all about diving in the deep end. Miles Roston has engineered and produced numerous recordings over the last two decades, but here he recalls his ‘first time’.

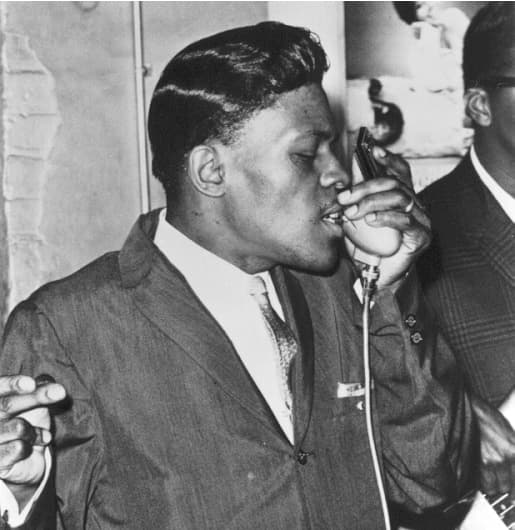

My first record as a producer was with Chicago blues legend, vocalist and harmonica player, Junior Wells. For those of you who’ve never heard of him, Junior is one of Chicago’s most famous sons of the blues. Born in Arkansas, Junior was singing and playing the harmonica on the streets of West Memphis by the age of nine. At age 12, he was caught stealing a $2 harmonica from a pawn shop and went to court, but after the judge heard the boy play a few notes, he paid for the instrument out of his own pocket. By the time I met him back in 1989, Junior was a dead-set legend of the blues harmonica, an icon.

I’d been producing demos for various artists in New York, when a record label rang and told me they’d found this seriously devoted blues guitarist named Brian Kramer, who played anywhere from clubs to the streets, and who wanted to make a collaborative album with Junior Wells. The record was to be an indie tribute to the elder statesman and major influence on rock ‘n’ roll, by Brian (just 24 years old) and some of the best musicians in NYC. There I was in the middle of it, myself only 25, wondering how I’d make it through the recording sessions without someone calling my bluff and asking, “Miles, what the hell are you doing here?”

I wasn’t a blues artist, but I’d grown up listening and playing guitar to the obvious – Robert Johnson, Little Walter, and Muddy Waters (with whom Junior played) – and the not so obvious: Skip James (that beautiful ghostly voice) and Mississippi John Hurt. So this was an ideal first record for me. And Junior had agreed, in principle, to his first recording in 13 years. Now all we had to do was get the deal done.

Which wasn’t that simple. It never is. But that’s the great thing about human beings: our ability to forget pain. No film or record goes easily or simply. Yet after I finish each one and say never again, someone calls me up or I get an idea, and it’s off to the races for more punishment. So I called Junior Wells’ manager, Marty Salzman, and after several heartbreaks where it felt like it would never happen, one day we all agreed: we had a record to make. And what record was that? Brian, Junior and I all agreed we wanted to make a classic record, not just of the times. At the time, Alligator Records was the dominant blues label in the US, trying to make the older blues artists appeal to modern audiences. Their mixes were very consistent, with a heavily compressed and reverberant ’80s snare sound. But even though we were living in the ’80s (albeit the tail end of them), we didn’t want to make a record that would date. We wanted to capture the joy of the musicians playing together juxtaposed against the deep sorrows and grooves of the blues. I wanted a sound I could be proud of 30 years later.

Though I was learning on the job, I did know that, blues legends or not, what we needed were great tunes and arrangements. Junior sent us a few songs he wanted to do, tunes like Pleading the Blues and What Mama Told Me. Brian and I started working on his own original tunes. We co-wrote one, and I contributed one other original. We also worked out a pace on the overall record, as one would a live set. So that sitting down and listening to the LP would feel like a perfect evening.

GUITAR PREP

Another part of production prep was working on Brian’s guitar picking. All of us think we’re ready the moment we have a chance to record, especially when we’re young. I did; I still do. But Brian had been playing a lot on the streets and in clubs, so he’d learned to focus on playing louder and less on finesse. On the sidewalk with traffic noise, that can pass with flying colours… even live in a bar, but not on a record. I wanted to invest as much of our limited budget as we could on recording one inspirational take after the other, not just capturing something technically passable. To Brian’s credit, he dedicated himself to honing his technique for recording.

THE BAND

In terms of musicians for the band, Brian had played around town and had gotten to know quite a few; I did too. The house band was sensational: Howie Wyeth (Bob Dylan’s drummer and a great ragtime piano player), Dan Hickey also on drums (later with They Might Be Giants), David Santos, an up-and-coming bassist (later playing with Elton John and John Fogerty), David Cohen on piano (Country Joe and the Fish), and of course Brian on guitar. Steve Jordan (Keith Richards/David Letterman Band) ended up contributing drums too, and for a few tracks we got the Uptown Horns (Tom Waits).

Our Holy Grail though was to get the great blues guitarist, Mick Taylor (formerly of the Rolling Stones). Mick would make the intergenerational feel of this record perfect; and there was no harm in trying. One of the house band members had a contact with Mick’s lawyer, as I remember it. I put in call after call, telling the lawyer we would love him to play, even on one track. I didn’t have big bucks to pay, but it was a tribute to Junior. Over and over, the lawyer told us Mick was busy or out of town, and that he’d get back to us. Every week or two I’d try again, with the same response. So no matter what, Mick wouldn’t be part of the original house band.

THE RECORDING SESSIONS

I knew a great old studio named Baby Monster, on Bleecker Street, and the idea was Junior would come to New York, and we’d record and mix it there with the best the city had to offer. The studio had an old MCI desk, a nice 24-track Studer, but most importantly a nice sloppy live room, where we could put the house band, and an Iso booth for Junior.

As we had a limited amount of time with Junior, and we also wanted him to be at his best on every song, we tracked some of Brian’s original tunes beforehand, for Junior to play on later. And it was a good way to ease into the record; for Brian, understandably nervous, and myself, also understandably nervous.

SESSION ONE

Everybody gathered in the main live room, except Brian, who was in the Iso booth: David Cohen at his piano, David Santos doing his tuning and Howie Wyeth working on the drum kit. And then we got a taste of what the rest of the recording process was going to be like.

As we got drum sounds on Howie, with his trademark tweed cap on, we got past the kick, snare, hi-hat, then moved onto the toms. Howie wouldn’t hit them. “Can we please hear the toms, Howie?” Again, reluctance. Finally I went in. Yes, I was a rookie producer, but what was the problem? The answer was simple from Howie’s point of view: “You can get sounds on the toms, but I won’t play them.” Good lesson; don’t bother miking instruments no-one’s going to use! We cut four tracks that night. And Howie, without touching the toms, did a brilliant solo on Brian’s two-step number – 32-20.

Then the Master finally arrived. A nervous Brian and I met a very tired Junior Wells in from the airport and drove him to his hotel. Being a producer (for the first time) felt a bit like hosting a party, and I wanted the party to go well. Junior was in his mid-60s now, had done 40 years of the “Chitlin” circuit [a string of music venues in the southern United States that sold chitlins (a traditional cheap spicy pork dish) and other soul food dishes. In the late ’50s and early ’60s these tours were crucial to black artists like B.B. King, Solomon Burke and James Brown], all the blues bars, normally touring in a van. As far as I was concerned, Junior deserved luxury; big budget record or not. So I’d booked him into the legendary Algonquin, a famed literati hotel. And looking around at the elegant trappings, he did appreciate it. He wanted a nap straight away, but we’d meet up later.

I picked him up for session one. He was ready except for one thing: he needed to find a nice shoe store. “Sure,” I told him, “tomorrow.” But he was adamant. Luckily there was one not far from the studio, and once in the store, Junior headed for the ladies department. Seeing that I was more than a little perplexed, he explained that wherever he went – first things first – he bought his mother a pair of shoes. He picked out a red pair, and we were on our way.

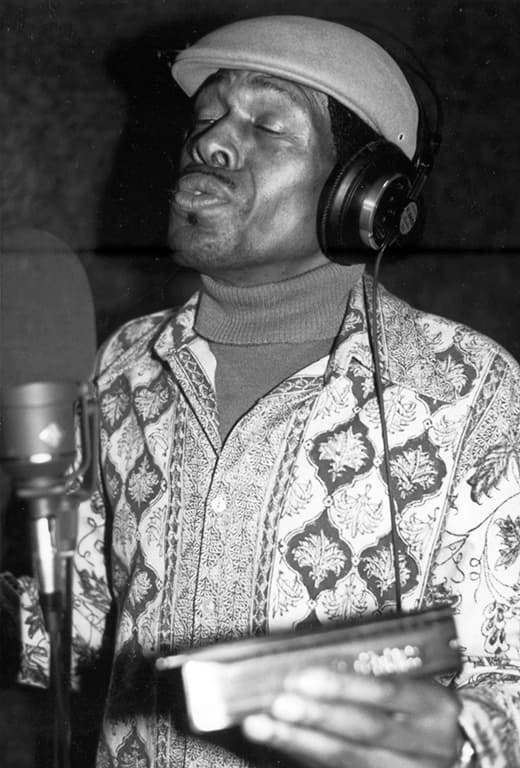

When we finally climbed the two flights of stairs to the studio, it was a hero’s welcome for Junior from the players and our engineer Gil Abarbanel, and Junior loved the adulation. Then we went to work. The drummer on the next two nights’ sessions was Dan Hickey. He used toms on his solos almost exclusively. (Later, Steve Jordan came in and returned to the snare-only routine!) David’s bass went through a DI box and my favourite old Pultec EPQ-1A EQs to give it a bit of oomph and juice. We used two old RCA 77 ribbon mics on David Cohen’s piano, and Brian’s blonde Stratocaster went through an old beat-up Ampeg amp. I don’t know why beat-up old tube amps sound just that extra bit more beautiful, but they do. Junior was in the Iso booth, and on his vocal and harmonica, we used a special old AKG C12.

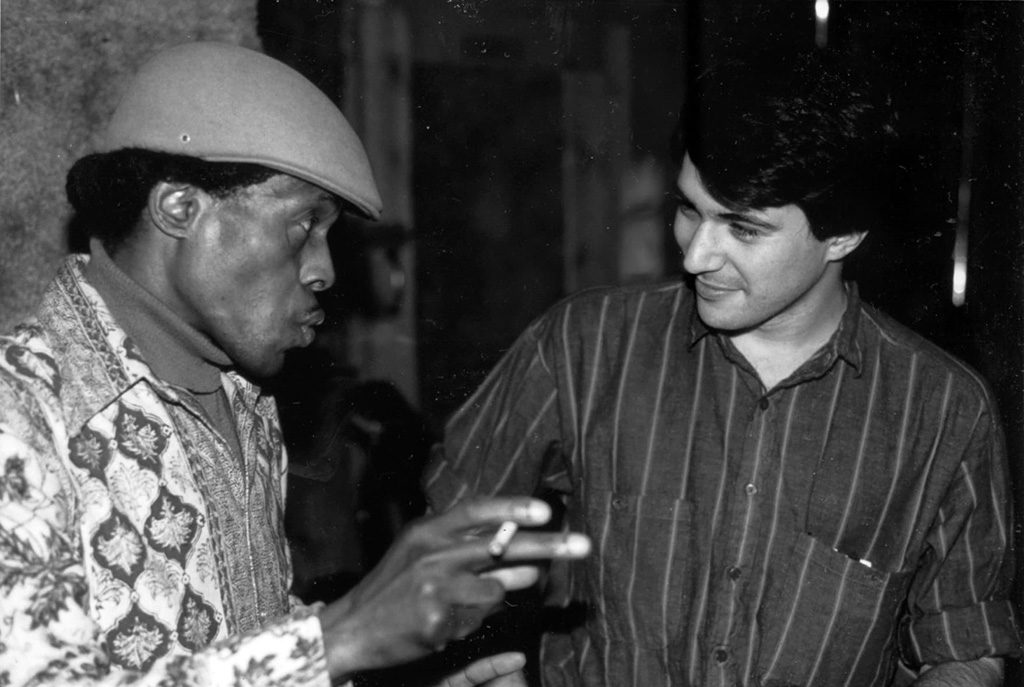

When Junior finally arrived at the studio it was to a hero’s welcome.

BAPTISM OF FIRE

That evening I became renown for a saying that has since stuck with me, that was tacked by the band to the studio door. “That was great. Can we do it again?” Yes, I was working with more seasoned musicians, but I had a responsibility to deliver the best record we could. Great as they were, they were always capable of greater: that I knew. And it wasn’t all milk and honey. Junior wasn’t always happy doing a re-take, and neither were the other players. I went head to head with him several times, and didn’t back down. And when I say head to head with a Chicago bluesmaster, I mean head to head.

On one track, What Mama Told Me, I wanted the intro absolutely spotless, to punch through. The song involved Junior on the harmonica doing a ‘call and response’ thing with the band. We tried it over and over, to the point where Junior was furious. But when we finally got the take I was satisfied with, and played it back in the control room, Junior broke into a huge grin and punched me lightly in the arm. And it set the precedent. We could argue like cat and dog, but we’d make it through. And, by the way, the rest of the record was like cat and dog.

One other incident was when Junior was soloing over one of Brian’s tunes. On his own vocal tracks, whatever the tune, Junior would lay down great raspy take after raspy take. But on this particular song Junior was overtired and didn’t really have it. I wanted to call the session and come back the next day; he insisted we go on, but he was way off his best and I knew it. Over and over, he’d lay down a tired and badly executed solo. It was very human of him, but he wouldn’t let it go. (Now, by the way, I would normally under those circumstances just call the session and start the next day – it’s amazing what sleep does for playing skills and the ears.)

The one thing I’d learned was that confrontation made him rise to the challenge, so I decided to take it up a notch. I could play a modicum of harmonica, so I got out of the control room, went into the Iso booth with Junior and asked him for his harp. He looked at me as if I was crazy. I insisted. He handed me the harmonica and with it I did something unbelievably arrogant. I asked Gil to roll tape and record. The track started, and I started to play, with Junior staring at me as if I’d lost my mind! I don’t think I sounded particularly good, but it was about a minute before Junior, in a fury, grabbed his harmonica back from me. Gil (to his credit and playing along) got on the talkback and said, “Great, Junior. Much better.” Junior just gave me a look. I left the Iso booth, we rolled tape, and he played brilliantly. We had a good laugh afterwards and a few days later, Junior went home, with the red shoes.

The rest of the record was also to be an inspiration: the Uptown Horns came in and did beautiful work; we kept the arrangements simple and strong. Brian’s guitar playing got stronger, cleaner and more passionate. His vocals had a warm sweetness that got better and better – more true to himself. Brian was a Brooklyn-born musician with a lot of talent and his own soul, but we all learn certain vocal or instrumental ticks, bits of phrases and phrasings, from our idols. Again, live in a bar, one can get away with it. In fact, audiences encourage it; the average crowd likes the familiar. But on record, it’s my job to get the artist to the most intimate level one can be – “tick-free”, purely oneself.

That was great, Mick (and it was). But can we do it again?

MEANWHILE BACK ON THE MICK TAYLOR FRONT…

As the producer of this album, and with the recording all but complete, I was still determined (naively or otherwise) to get Mick in on at least one session, but over and over, his lawyer kept pushing us off. I don’t remember how, but someone among the musicians got us Mick’s home number. Stammering, I called him up and told him we were trying to honour Junior Wells and the blues with our younger artist Brian. I apologised for calling him at home, but said we’d been trying to get him through his lawyer for weeks. And now we were literally out of time. He interrupted and said he’d love to come. When was a good time? He said his lawyer had not even told him about the record.

When the other musicians heard Mick Taylor was going to be coming in, they insisted on being there. Mick arrived with his trademark Les Paul; we plugged him in (sorry, I don’t remember which amp) and sat down in the control room together as he played against the tracks. And here’s where my stock phrase came in (and I remember the shocked look from David Santos!): “That was great, Mick (and it was). But can we do it again?” (Because it can be even better.)

Rather than being pissed off at this immature 25 year old, Mick did just get better and better (brilliant to start with). Later, we ended up co-writing a few songs and playing together. To me, Mick had the sweetest sounding guitar, and voice. He was also a great writer, and I wish he’d become the household name that Eric Clapton ended up becoming.

At the time, the producer/engineer was an anomaly. Producers and engineers were two people with different roles. This gave the producer the luxury of listening to takes with full attention, beyond focusing on the arrangements etc. The engineer could focus on miking techniques and the EQ and the quality of the sound. This helped in working with someone like Mick Taylor, giving him full attention and being able to choose which was the take. We had 24 tracks on two-inch tape. That meant we had to make decisions then and there, which I still don’t think is a bad thing. Then the mix becomes that – a mix, not a time for choosing between umpteen takes.

The aftermath of production was disappointing. Inexperienced but not dedicated, the label did a lacklustre job of promotion. They counted on Junior Wells’ fans hearing of it through the grapevine. But we got good reviews, and I still play the record and still think it sounds damn good. It doesn’t have that ’80s sheen. It sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday. And that’s the point.

Junior Wells has since passed away. He was a legend in myth, a legend in life, and I’m sure is kicking up a fuss wherever he is now. Mick Taylor, still touring, has never really broken the barrier to mainstream success. The Uptown Horns continued to play; Chris Botti on trumpet, their youngest member, became quite renowned in his own right after playing with Paul Simon. Brian moved to Sweden, where he is carving out a reputable career as a blues musician; and has in fact just released a new record.

But Junior taught me what it was to be a producer and a musician. How to get tough, while at the same time getting at that sweet and tender soul down deep. And that was the right role of toughness, to protect the sweet and tender underneath. No matter whether you’re 25 or in your 60s.

Brian Kramer visited New York last year, and we played a few songs together at some dive on the Bowery: as it should be. Some of the songs we recorded 15 years ago. It brought back Junior Wells memories, as if indeed it were yesterday. I remembered talking to Junior not long after we finished the record, and he was back in Chicago. His mother did like those red shoes. I’m glad I had some little hand in buying them.

RESPONSES