Danger Mouse: Producer of the Decade

Danger Mouse is a triple-threat: producer, songwriter and musician, and an inspiration to budding bedroom producers with a few song ideas and a computer. Our Producer of the Decade has come a long way in 10 years.

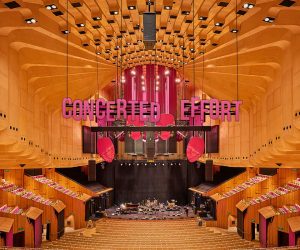

Photography: Ryan Schude

Bedrooms, garages and basements are the traditional breeding grounds of genius. Unlike high-rise corner offices, there are no approval committees, no business development plans to adhere to, no one to say, ‘No’ — just you and your ideas. If you’ve got the talent, the time, the idea and the will, you’ve got everything you need. And a computer, of course.

Before Facebook had a billion users and contracted superstar architect Frank Gehry to design its audacious new Palo Alto headquarters, it was the product of a university student in a dorm room. And the Silicon Valley trope of up-all-night, 72-hour lock-in programming marathons isn’t too far from how some of the world’s best records are made.

Long hours, late nights, living in the studio. It’s a coming of age, incubation process for musical ideas. Shutting out any outside influence, and pouring everything you’ve got into a concept.

It’s how Danger Mouse, née Brian Burton, became infamous.

In 2004, the producer locked himself in his second-storey bedroom. Just him, his bed, Sony’s Acid on a PC and two albums’ worth of gold source material. Seven days later, he emerged with a mash-up collage comprising a cappella vocals from Jay Z’s The Black Album and music from The Beatles’ The White Album. The Grey Album, as it was named, not only staked his place in popular music culture, but helped shape the worldwide copyright debate.

EMI took umbrage with the unlicensed use, and ordered the album to be taken down. But the mash-up — originally intended for friends Burton knew wouldn’t be offended by the ‘sacrilegious’ slicing and dicing of Beatles material — was downloaded over 100,000 times in 24 hours when, on a day dubbed Grey Tuesday, an independent group coordinated a mass spread of the album across 170 websites.

Even Sir Paul was into it: “I didn’t mind when something like that happened with The Grey Album,” he commented in the BBC documentary The Beatles and Black Music. “But the record company minded. They put up a fuss. But it was like, ‘Take it easy guys, it’s a tribute.’”

The Grey Album brought Burton notoriety, but his trajectory since then has been continually rising, both as a producer and a musician. He has been one half of two high-profile duos: Gnarls Barkley with Cee-Lo Green, who had the mega-hit Crazy; and Broken Bells with The Shins’ James Mercer. Over five years, he and composer Daniel Luppi patiently reconvened the original Cantori Moderni choir that sung the score to The Good, The Bad & The Ugly, and a cast of Italian musicians from the Ennio Morricone era, to record an album inspired by spaghetti western soundtracks with Jack White and Norah Jones.

Burton has also produced albums for Damon Albarn’s Gorillaz [Demon Days] and The Good, The Bad & The Queen projects; Beck’s Modern Guilt; The Black Keys’ breakthrough album Attack & Release as well as El Camino; Norah Jones’Little Broken Hearts; Portugal, The Man’s Evil Friends; Dark Night of the Soul, and a collection of songs by the late Mark Linkous of Sparklehorse recorded with a rotating cast of vocalists from Iggy Pop to Suzanne Vega. Now, in between touring the second Broken Bells record, he’s tying up the production of U2’s next album, arguably still the biggest band in the world.

He’s a long way from the bedroom.

GREY AREA

Probably the biggest misconception about Burton — perhaps because he’s American, has an afro, and The Grey Album was necessarily stylistically skewed towards Jay Z’s raps — is that he was always purely a hip hop producer and DJ, and somehow stumbled into rock music. Really it was the other way around.

The DJ ‘thing’ “is kind of a misconception,” said Burton. “What really happened was when I was 19 in college, I decided to try music out. I never really thought music was art, I just thought it was entertainment. But I never wanted to be an entertainer, I just wanted to be an artist and thought more about making films or being a comic book artist. Then I realised you could make music in an ‘art’ way.

“So I started getting equipment. I bought a cheap keyboard, a cheap four-track off a friend, a guitar and a sampler. And I hooked all those up in my dorm room and started playing stuff in and making loops. I didn’t play any live drums, it was all samples, keyboards and guitars.

“I had no training. I didn’t know what I was doing, I just fumbled around with it. I made my own soundtrack-sounding instrumental albums — basically, things I could make on my own because I was afraid to work with other people and embarrass myself. Every once in a while I would get someone who could play guitar better than me to help out.”

A stint DJing for his college radio station and seeing friends making good money on the club DJ circuit led Burton to get some equipment of his own. But it was strictly party DJing — no tricks, nothing fancy. “I just played records that made people dance and that was it,” said Burton. “I wasn’t a very skilled DJ, I can mix a record and had good taste, but I just liked being able to pick what people would want to hear next. I DJ’d to make money so I could make my music at home.

“So that’s how I started, making rudimentary versions of the Rome album. Except that I didn’t have nearly the amount of great musicians and didn’t know how to write songs so much back then either.”

I never wanted to use computers. I thought it was cheating, I didn’t think it was pure… I didn’t know what I was talking about

NOT VERY PC

It wasn’t until a few years later that Burton really started to make headway with his music. And it was all due to the one thing he’d always avoided — a computer.

Burton: “I never wanted to use computers. For years, I refused to use them. Even though I was using a digital eight-track, I still didn’t use a computer. I didn’t use one until I was probably 23 or 24. I thought it was cheating, I didn’t think it was pure… I didn’t know what I was talking about.

“When I was in London, a friend of mine saw how I was working and suggested I try it. He gave me a copy of Acid and showed me how to use it for a day or two. The first things I ever did on a computer were three hip-hoppy instrumental pieces, despite never having done hip hop before. I put them on a CD and I sent them to this record label guy I’d just met, and he signed it right away. Oh man!

“The way my head works with music, the computer allows me to react very quickly to things, to mistakes. And if I’m getting on something, I can hear the end of it in my head and figure a way to get there a lot quicker when using a computer program. So I was able to do a lot more and not fatigue from listening to stuff over and over again until I got it right.”

The label he signed to was Lex Records, an imprint of the cult label Warp Records. Before The Grey Album, Burton had already released Ghetto Pop Life with rapper Jemini the Gifted One on Lex, and had started working on Gnarls Barkley with Cee-Lo. But when The Grey Album landed Burton started receiving offers to produce, which he was bemused by. “I was like, ‘Why would you offer me this?’” said Burton. “The Grey Album was really just a remix record. I mean it was intricate, took me a long time to do, and I was proud of it. But why would you want me to do that, just because I did this? It didn’t even make any sense.”

BLUR OF INSPIRATION

There are some offers you just can’t refuse though. And while The Grey Album propelled him into the popular consciousness, when Damon Albarn from Blur came knocking, he provided Burton with the necessary stepping stone to become one of the defining producers of the generation.

“After The Grey Album came out, Damon got in touch and I met with him for a week in England,” said Burton. “At first, it didn’t make sense to me. I didn’t know what he saw. But I think it was much less about what I’d done and much more about the week we spent together making stuff. He tried me out.

“It was the first thing I ever produced. The idea of producing and what producing was, means different things to different people. For me I thought producing was making all the music, and that’s what I was doing. In hip hop music, the guy who makes all the music, and doesn’t rap, he produces it. Whereas in rock music, the producer doesn’t even need to make any music, he can just give his opinion or tell people to play faster or slower, or a new chorus, how to record and what sounds to use. Those are different approaches and I never knew about the other side. I just made my own music in my bedroom. That’s how I pretty much did all the music up until Gorillaz. But I didn’t tell Damon how inexperienced I was. You just go do it.”

So, what did that dynamic look like for a producer who didn’t have the usual wealth of experience under his belt? Luckily, Albarn didn’t need a lot of hand holding.

Burton: “I did make a lot of beats and play some music, but he already had demos for a lot of it. It was more about how we interpreted a low quality demo into a whole song. He knew how to do that, I didn’t really. I’d never gone through that process before, but when we would start the song over I would just get into my thing and run with it.

“It worked out well mainly because Damon did it with me. He really empowered me, but he also had his own opinions. I learned how to work with him and get what I was looking to get out of it. It was a fun process. It could have gone a lot of different ways, but luckily for me, the first thing I produced went really well because of Damon.

“I hadn’t been in a big studio working before and even that to be honest was pretty humbling. Up to that point, I’d only been in home and bedroom studios. It wasn’t really big, his original ’13’ studio [set up for Blur’s album of the same name — Ed], but it had a lot of stuff all over the place and was a very creative environment that was easy to work in.

“Day one, I thought I was going to meet him to see if we got along as people. But he said, ‘Hey, let’s go to the studio tomorrow.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ But I’d never worked on anything but my own equipment, so I had no idea how to use any of the stuff they had. I didn’t bring any of my equipment with me.

“I didn’t know how to use any of the drum machines or keyboards he had there, so I had to just try and figure it out. He had these great engineers, Tom Girling and James Cox, who engineered the record. They helped out, but I didn’t know how to use a mixing board or any of that stuff. I was in there fumbling around, trying to figure it out. I didn’t want him to know that. I was only 26.”

A HIT ON ACID

Burton has made a habit of developing artistic relationships on a try-it-and-see basis. Just getting together with artists to see how the relationship feels. No expectations, no contracts, just start working.

In 2007, when he showed up to Beck’s house to dry run a potential musical partnership for what ended up being Modern Guilt, Acid played a big role in helping Burton’s visions translate into production. His proficiency with Acid became his greatest asset, and he began to use it as just another instrument. In fact, it was the only instrument he took.

Burton: “I showed up to Beck’s house without a guitar or keyboard, just my laptop that had Acid on it. Anything we made, I could put into Acid and turn it into something. Or if I had beats or something else I wanted to start messing with, I had them there as well, so Acid was my instrument in a lot of ways at that time.”

And it shows. The record is an amalgamation of live recording and samples intertwining Beck’s eclecticism with an ear for retro rock. Case in point, lead single Gamma Ray kicks off with an Acid drum loop combined with a simple guitar progression. But you’d be hard pressed to put it anywhere but in the alt rock genre.

These days, he rarely uses the program, preferring to sit down at a piano or with a guitar when he’s figuring out a song. But he’s thinking of a way to go back and use Acid a little bit more, considering how useful it’s been for him. “I haven’t sampled a lot in the last four or five years,” said Burton. “Since the last Gnarls record really. I’m thinking about getting back into it more.”

KRAFTING INFLUENCES

Much has been made of Burton’s affinity for The Beatles. But, he says, most of his early influences were ’60s and ’70s soul and R’n’B, and ’80s pop. He got into classic rock a bit later in his musical life, and if he had to pick his biggest influence, it would actually be Kraftwerk.

Burton’s ability to fuse soulful styles with the efficiency of German minimalism is undoubtedly a big part of what attracts musicians to his services. But he still considers himself “a song person more than a sound person, for better or worse.”

Burton: “It’s more how a song makes me feel. Does it break my heart a little bit? Does it have that melancholy quality to it? Does it do something to me in that way? I gravitate towards the darker side of music. Unique is great, but sometimes I don’t mind if I’ve heard something similar before if I can get a new feeling from it. That’s good too.”

It’s here where Burton differs from a lot of producers. Many producers see their role as paving the way for the artist to deliver their best performance; for them to showcase not only their talent, but their vision for the song. For Burton, he’d rather you not know who played it at all.

“The main thing for me is what you visualise,” he explained. “It’s always been important for the project I’m working on to not sound like musicians playing instruments, because I don’t want people to visualise someone playing guitar and drums and bass. Even if it’s obviously guitar, drums or bass. Whatever the part is, and how it sounds, should make somebody think of something else — a place, a dream — not the people who made the music.

“It’s hard for me to put my finger on, but I know when I hear it, and I know when it’s not there.

“Sometimes if you blow out some drums and you overly push, distress and distort them, then you hear chaos and a certain kind of pace or urgency. You’re not hearing the way it was put together. You start to think of something else. You don’t think of a drummer, you hear some kind of anger or madness and you mix that with something really lush and really beautiful like a xylophone and then you’re thinking of something else, but you’re not thinking of somebody playing the drums.”

It’s this idea of the gradual accumulation of parts influencing the outcome that Burton is most interested in. In the same way an engineer crafts space in the spectrum or paints elements with width and depth in the soundstage, Burton as a producer is working with the sum of parts.

Burton: “I can’t tell you what it’s supposed to look like, but I know it’s not supposed to look like people playing instruments and recording them.”

I can’t tell you what it’s supposed to look like, but I know it’s not supposed to look like people playing instruments and recording them

THE HIDDEN PLAYERS

Burton is the first to admit the genesis of this philosophy was more to do with his lack of playing ability. “I didn’t want to depend on my musicianship to impress anybody,” he said. “That’s probably why I started out doing it that way. I just wanted to make people feel something and if you’re not a really amazing player, you have to find an interesting way of doing it.”

Having now worked with a lot of talented musicians, he’s not blind to their strengths either. The biggest exception to Burton’s ‘rule’ occurred the second time he worked with Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney from The Black Keys. His philosophies became jumbled up with the duo’s acuity for great performances.

Burton: “El Camino was all from scratch. We’d just go in and flesh out ideas together. Ultimately though, no matter who had whatever idea, the two of them would usually go in and start playing it.

“I had never done that before. Even working with other people, when I write things it’s not about the performance, it’s just about what you actually come up with. It wasn’t about going into the room and starting over or rehearsing it together. But watching how they did it, that made it even more different from the way I’ve written with people in the past.

“That’s what made it more of a special record, because it had melodies, and a lot of catchy things going on, yet it still sounded like the two guys for the most part. That was a new experience for me, writing something that way and watching them flesh out what was written in their own Black Keys way.”

The sessions for Rome took a similar turn. While Daniel Luppi and Burton provided transcribed scores to follow, arguing against the intuition of the Italian musicians who’d played on the original Spaghetti western scores seemed unwise.

Burton: “I’d have my own drum pattern, bass line, chord sequence and melodies on top, and then get them transcribed. A lot of stuff was written on paper in front of them while they were playing. But the key guys would remember the chords or the way it goes and just start figuring it out in their own way. Sometimes those songs would come to light in a way I had never heard, because they were interpreting them in a way they felt it should go, or what their style was.”

The Good, The Bad & The Queen project, which featured Fela Kuti drummer Tony Allen, The Clash bassist Paul Simonon, and The Verve guitarist Simon Tong alongside Albarn, tested Burton’s resolve.

“Everybody in the band was really great at what they did. Overall though, it was a dream-like record for me. Even though there were elements of live playing, it would come in and out of that dream.

“It was weird because you have all these great individual musicians and I didn’t know if I was doing it wrong or not, to make it so dream-like. Will people just want to hear a band play? But I didn’t want to hear that for a whole record. I wanted to hear the fantasy of the whole thing.”

ENGINEERING A DREAM

When Burton thinks back to those sessions though, he couldn’t imagine them without the creative engineering of Jason Cox helping drive that dream.

Burton: “He’s an amazing engineer. At the time, I hadn’t really had much experience with engineers to know how really good he was. But looking back, I can see that now.

“I can’t think about The Good, the Bad & the Queen without him. A big part of the sound of that record comes from what Jason was doing as an engineer. He’s amazing with spring reverbs and bouncing around delays. It developed the sound of the record.

“Work with a really good engineer, that’s the main thing. I engineered my own records up until a point, but I don’t think I did really well at it, and I didn’t do anything in a professional way or in a professional studio. The whole trick is to make people think it’s not in the bedroom. Looking back now, I can tell it was in the bedroom, but I thought I was fooling people.”

These days, Burton’s partner in crime is Kennie Takahashi, who Burton describes as his “ultimate engineer”. If you were sticking to the Danger Mouse characterisation, Takahashi would be Ernest Penfold — the bespectacled hamster sidekick who always finds himself in need of rescue. But in this saga, Takahashi is the one solving all the tricky problems.

The pair met when Burton was working with Martina Topley-Bird in 2007: “I was getting ready to do her record in Los Angeles and we used a service to find a studio that would give us a good deal, because it was an independent record. We wound up at Glenwood Place, which is a really nice studio off Burbank, and they matched me up with Kennie. He was the house engineer and we got along amazingly. We worked together on that album and after that he’s come with me on everything.

“We have very similar qualities, but I can’t do anything like he can do on ProTools. He’s so, so fast.

“I think about what would have happened if he wasn’t around back then. I know what I do wouldn’t be where it is. I shudder to think about that. He’s one of the people that’s been a huge part of what I do.”

And for Takahashi, it’s been a boon. He’s not only engineered pretty much everything Burton has worked on since Topley-Bird, he’s also mixed Modern Guilt and assisted with the mixing on a lot of the records too.

THE MOUSE THAT ROARED

Burton’s preferred mode of working is somewhat bullish. But it’s a big part of what makes him a sought-after producer. He has vision. And he had it even way back in his bedroom. It’s what Albarn saw, and it’s what continues to come through in each production.

The way he eases into musical partnerships is as much about the artist feeling him out as he them. He’s only interested in working with someone if they’re willing to budge, or at least meet him some of the way.

Burton: “Sometimes I hear an artist and go, ‘Okay, this how I’d do it, this is the record I’d like to hear from them.’ And if they want to know what that record would be then they should hire me. But the record I want to hear from them isn’t necessarily going to be the biggest selling record. It might be their best record or their worst one, I don’t know. But when I hear someone’s voice and what they can do, it makes me think this is what I’d love to do, these are the things I’d like to feel from them.”

These days, you won’t find him in his bedroom nearly as much.

RESPONSES