Slash!

He’s the man with the hat, but it’s what lies underneath it that really counts. Engineer Eric Valentine talks about Slash’s recent solo album, Slash.

“When I first met Slash to talk about his solo album,” recalls Eric Valentine, “I immediately told him the only way I wanted to do it was to approach it like a classic rock record: get great musicians, rehearse the songs properly, and record them on tape machines. There’s one particular vintage tape machine that I wanted to use for drums and bass to get that classic ’60s rock sound, and for overdubs I then wanted to use a more modern tape machine that can punch in and out. My idea was to make it really simple, with a great drum sound and one guitar in one speaker and another guitar in the other speaker, so you can really hear performances. I didn’t want to hear just a wall of guitar sounds, I wanted to be able to hear Slash playing guitar. He seemed really excited about that.”

Slash was excited enough to entrust Valentine with the engineering, mixing, and producing of his first genuine solo album. Given Slash’s patchy commercial success since leaving Guns N’ Roses in 1996 – he formed the bands Snakepit and Velvet Revolver and only the latter’s Contraband album enjoyed mega success – and the fact that Valentine’s most recent successes had not been with heavy rock but with hit parade-friendly albums by Maroon 5 and The All-American Rejects, the collaboration doesn’t at first sight appear an obvious fit. However, whatever risk Slash may have taken in hiring Valentine has paid off in spades: the collaboration, simply named Slash, has reached No. 3 in the US and topped it in many other countries.

It’s easy to understand why. Not only does Slash feature a number of high-profile singers, amongst them Ozzy Osbourne, Andrew Stockdale, Lemmy, Iggy Pop, and, err, Fergie and Maroon 5’s Adam Levine, plus four of the five members of the most successful incarnation of Guns N’ Roses, the music itself seriously rocks out with much full-on guitar work that lifts an impressive amount of good songs to even higher levels.

The most immediately striking aspect of Slash is its in-your-face sound, which harks back to the golden days of classic rock ‘n’ roll, while at the same time being thoroughly modern. The album was recorded and mixed at Valentine’s Barefoot Studios in Los Angeles where ancient tape machines and other vintage equipment – not to mention Valentine’s and Slash’s respective skills – conspired to produce some kick-arse results. With Scully and Studer tape machines, EMI and custom desks, an enormous array of valve, ribbon, and other microphones, and all manner of vintage and funky and obscure outboard, Barefoot Studios is clearly the domain of someone in love with analogue recording. So the main question to be answered in this article is simply this: ‘Mr Valentine, what’s with all the old and clunky and clumsy and often unreliable stuff, and how did you manage to produce results with it that put state-of-the-art 21st century DAWs to shame?’

“Modern, digitally recorded albums are an abusive sonic experience,” responds Valentine cheerfully, laying down his opening gambit. “The whole advent of digital recording has affected many aspects of the music industry and of contemporary recording, mostly in an unfavourable way. It has contributed to the overall decline of the recording industry, in part because listening to digital is less satisfying than listening to analogue. To my ears, digital stuff has an uncomfortable buzzy high end that I find very difficult to listen to or work with. Digital has the remarkable ability to sound dull and harsh at the same time, and I have to admit that HD doesn’t sound dramatically different to me. Of course, my formative years of getting into music and recording were during the analogue days, so I’m aware that I’m romantically attached to that sound and that way of doing things. But there’s also real truth in the fact that modern, digital records just don’t have the same sonic effect as analogue records. When I was growing up and my favourite bands had a new record out, I’d get it, put it on my turntable, and listen to it probably 10 times in a row. They were great sounding classic rock records, and I’d listen to them over and over. I simply can’t do that with modern records. They’re just way too fatiguing to listen to for a long time.”

EXTREME VIEWS

For those of you about to turn the page, thinking that Valentine is yet another stuck-in-the-past old fogey, there are a few things that should give pause for thought and a reason to read on. For starters, Valentine is far from old. At 41, he’s in his prime and not part of an older generation that’s now reaching pensionable age. Valentine, who grew up in the San Fransisco Bay Area, got into recording as a young teenager in the early ’80s, first doing sound on sound with “two compact cassette recorders and a little Radio Shack mixer,” then using a four-track Tascam portastudio. These were not the heydays of analogue, but a time when digital recording was beginning to make inroads; the CD was launched, and computer technology was introduced in popular music. Second, in keeping with his younger age, Valentine’s cultural outlook is not that of the precious, high-end, musical connoisseur. Instead, as a drummer he was part of the hard rock band T-Ride, and as an engineer and producer he has worked with urban (Paris), ska-punk (Smash Mouth), post-grunge (Third Eye Blind, Lostprophets), heavy guitar (Joe Satriani), and punk-pop (Good Charlotte) acts. In other words, Valentine has always been in touch with the spirit of the times. And third, of course, there’s the gobsmacking (almost literally) sound of Slash’s Slash. Oh, and the little detail of Valentine waxing lyrically about working with DAWs… but more on that a little later.

“I suppose I have some pretty extreme views on analogue versus digital recording,” notes Valentine. Indeed, in this day and age, when even many analogue dinosaurs succumb to the convenience of digital, it turns out that Valentine’s enthusiasm for analogue isn’t only to do with sound quality, he also sings the praises of the analogue way of working.

“Making records with tape machines has always felt more like an actual craft to me,” he says. “I’m self-taught and learned my craft in the studio that I set up during my T-Ride days: it was called H.O.S. (an acronym for “Hunk Of Shit”) and by the ’90s I’d been in six locations around the Bay area. I had a Fostex B16 at one stage, and a Neve 8038 desk with 1081 EQs. The latter took up too much space and was not practical for mixing, so I switched to a Neve 8128 in 1997. In 2000 I bought Crystal Studios here in Los Angeles, the main reason being that I wanted a large tracking room, and I transformed the studio into Barefoot Recording. I’ve had several desks here, among them a Neve 88R and since 2006 I’ve been designing and building my own custom console, which is finally now complete.”

CRYSTAL BALL

Crystal Industries Recording Studio was a legendary place where artists like Barbra Streisand, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Wonder, and Eric Clapton were recorded during the late ’60s and ’70s. It had fallen into disrepair when Valentine bought it and required major renovation. Crystal blossomed during the heyday of analogue. Now that it’s the 21st century, surely something has changed on the equipment front at Barefoot?

“I do make records using a computer,” admits Valentine. “I started using Logic and then switched to ProTools in 1997, with the advent of Beat Detective, but working with computers is a completely different process that leads to completely different results. I’ve been trying to figure out ways of finishing records without using a tape recorder, but it doesn’t really work for me. It’s just too disorientating. I just went through another project that I started doing on a computer, and halfway through I had to get the tape machines going.

“I now record in different ways. Sometimes I’ll start a project in ProTools and use the benefit of digital editing to comp’ performances, and after organising everything in the computer I’ll transfer the project to a tape machine and mix from there. I did that with the Lostprophets record. It seems an appropriate way of working for rock band projects. For more pop-style projects, where potentially a lot of arrangement edits are made close to finishing, I capture the sound on analogue first and then transfer it to a computer. I ended up using that approach for The All-American Rejects single, Gives You hell.”

I always tell mastering engineers: ‘I don’t care if we have the loudest record, I want it to be the best sounding record

SINK OR SYNC?

During the mixing of the Slash album, Eric Valentine ran two multi-track tape recorders and a ProTools rig simultaneously. Asked if this resulted in any sync issues seemed to hit a sore spot. “Yes, sync was a huge problem,” exclaimed Valentine, “largely because our friends over at Digidesign have destroyed the SMPTE sync function in ProTools 8, so I was constantly wrestling with that. I had to check the sync of the tape machines with ProTools constantly, using my ears to make sure the snare on the tape and in ProTools were really tight. The thing they’ve screwed up in ProTools 8 is that the SMPTE sync doesn’t accommodate delay compensation any more. So every time there’s a change in the amount of delay compensation, it changes the SMPTE sync. This definitely wasn’t a problem in version 7, but unfortunately I couldn’t go back to that, because I upgraded my soundcards and computer to an Intel machine and couldn’t get an install of 7 to work on my new hardware. So I was stuck with it. It was really distracting and tiring to always be wondering in the back of my mind whether the tape machines and ProTools were still in sync and constantly adjusting the sync offset. But we managed to fight our way through it.”

TWO (MULTI-TRACK) RECORDING

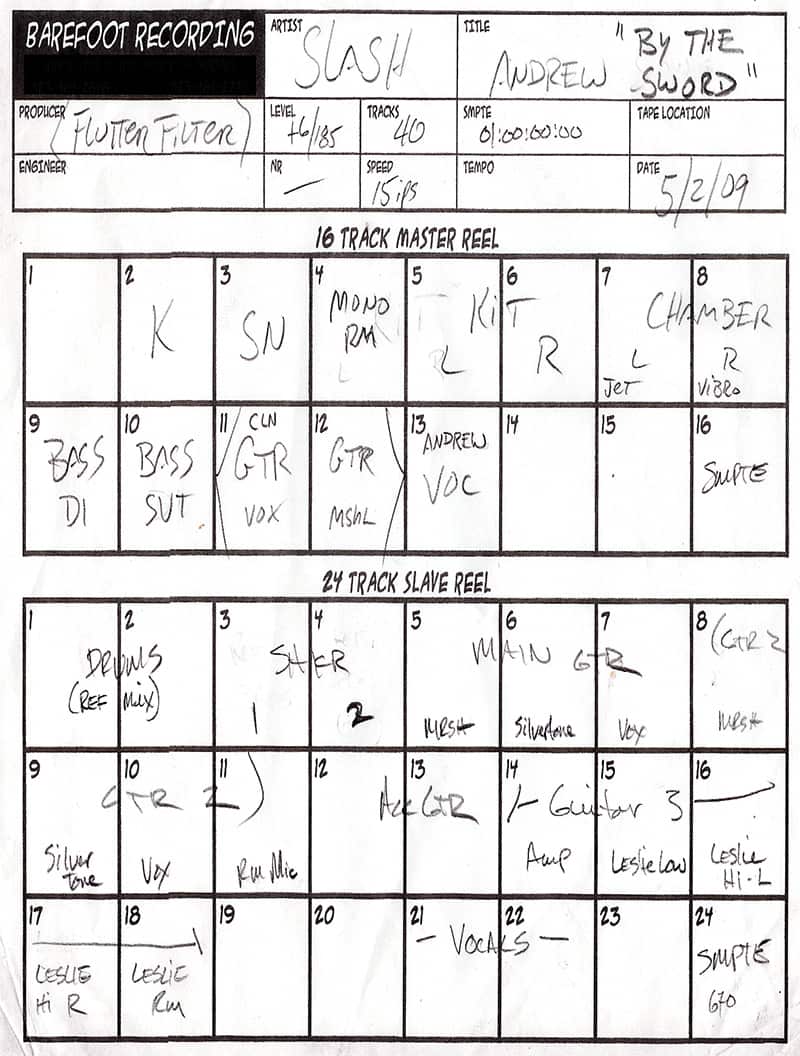

Interestingly, Slash’s Slash was made with neither of the above-described methods. Instead, Valentine recorded the players live to two of his favourite multi-track tape recorders, editing the music on them as well, and using ProTools for recording vocals, as an effects box, and for backups. He explains the reasons why later in the article. But first he took the story of how he recorded Slash and mixed the album’s first single, By The Sword, from the top:

“Slash and I met through some mutual acquaintances. I’d never met him, and I’d of course heard all the infamous stories about him from the past, so for our first meeting I wasn’t sure what to expect. I didn’t know whether there would be this train-wreck with a top hat careening into the restaurant or what. Instead he was incredibly composed, very focused and very easy to talk to. He knew this record was going to be eclectic, with different singers on each song, and I think he was looking for someone who could approach each song in a more individualised way and who could accommodate different stylistic approaches. He also said that he’d always made records with tape machines, and that the computer approach of playing in the studio and later finding that his parts had been moved or changed or otherwise edited wasn’t something he was comfortable with. So the approach I suggested was really far more along the lines of what he was used to.

“We started recording in April of 2009 and worked on and off for almost a year on the record. Scheduling was incredibly complicated, because of variations in his schedule and those of the various singers. In that regard, having my own facility was a huge asset.

“Everyone involved really knew what they were doing, so there wasn’t much pre-production necessary. Slash is an amazing songwriter and arranger and he’d recorded instrumental demo versions of all his songs at Chris Flores’ studio. He sent them to the singers, and they then wrote their vocal lines and lyrics and recorded these to the MP3 of the song in question. “In a handful of cases the singer went to Chris’s studio and they worked on the demo vocals there. Slash intentionally wanted to record the demos quickly and roughly, using drum machines and so on, to avoid getting too attached to these early versions.

“We nonetheless used some of the original keyboard stuff that Chris Flores had done for a ‘radio’ version of Fergie’s Beautiful Dangerous. Also, Slash’s vision and demo arrangements were so clear that most of the original demo arrangements didn’t change much. What changes he did make worked really well for the singers, and I think he pulled some really cool stuff out of them, some of it the best I’ve heard them do in a long time. So a lot of times the vocals and arrangements were already pretty worked out by the time Slash came to Barefoot. He and I would listen to the vocals and arrangements and make decisions about what worked and what didn’t, or what could be better. We then got [bassist] Chris Chaney and [drummer] John Freese in, and we finalised the arrangement with three of them in the studio. Everybody would be throwing around ideas and we’d make sure the demo parts translated into a group of human beings playing in a room.”

EXTRAORDINARILY LOUD

Valentine: “The process of recording was Slash, Josh, and Chris playing together in my main recording area, facing each other, playing the songs live. A big part of Slash’s sound is having his amplifier playing extraordinarily loud, so we had to have that in a separate room. This meant he and the band were recording with headphones, even though Slash hates them. It took them maybe three to four hours for each song to work out the arrangement and play a couple of takes, and from there I’d edit the best bits to get the master. We’d typically take about three days to record the music for an entire song. The first day we’d get the arrangements and record bass, drums and the basic guitar part. Once these were recorded and I’d edited the master, I’d copy it to a slave reel and the next day Slash would do his overdubs to that. Because the headphones make it hard for him to feel what he’s playing, for his overdubs I’d set up a live kind of thing in the control room. I have these big Urei 813 monitors, which are almost like live monitors, and I’d just crank them way up. Sometimes I’d be wearing ear protection while Slash was doing overdubs in the room with me. In that situation he was incredibly accurate and consistent. On the third day we’d usually record the singer.”

CHAIN OF COMMAND

In tracing the signal chains that Valentine used to record Slash and his musicians, Valentine revealed some unusual microphone choices, mic placements, and antique recording media. “I recorded the drums really simply, usually with a classic rock four-mic setup; with a mic on the snare, in front of the kick drum, a mic that hovers above the hi-hat and one that hovers on the other side, above the floor tom and crash cymbal. Sometimes I’d supplement that with a chamber mic and/or I’d put a Shure SM57 in front of the drum kit and send that to some guitar amps that had spring reverbs and I’d mic the amps and get a great distorted, reverby sound that blended in really well. The specific drum mics I used were mostly an SM57 on or an old Altec 633A ‘saltshaker’ on the snare, a Neumann U67 on the kick and the two overheads would be AKG C12As.”

“As for the bass and guitar, the bass cabinet was mostly an Ampeg SVT 8×10, which was in a separate room, with a Neumann U47 FET and a Sennheiser MD421 placed in front of it. The 47 FET generally had a warmer and more natural sound than the 421. The guitar is very straightforward with Slash. He plays one electric guitar for everything; a replica 1959 Les Paul Standard made by Chris Derrig that he obtained when recording Appetite For Destruction. I used a few different mics on his very loud cabinets, mostly an SM57, but sometimes a Sennheiser 421, sometimes a Beyer M160 ribbon if we wanted it to sound a little warmer and smoother. He has a particular Marshall 412 cabinet that he really likes that has great low end. We would almost always have that rig going because he’s very comfortable with it, and occasionally I’d mult’ the signal from his guitar to other amps, like a Vox AC30 and an old Silvertone to blend in and get different textures that can help identify different parts.”

GREAT COMPUTERS

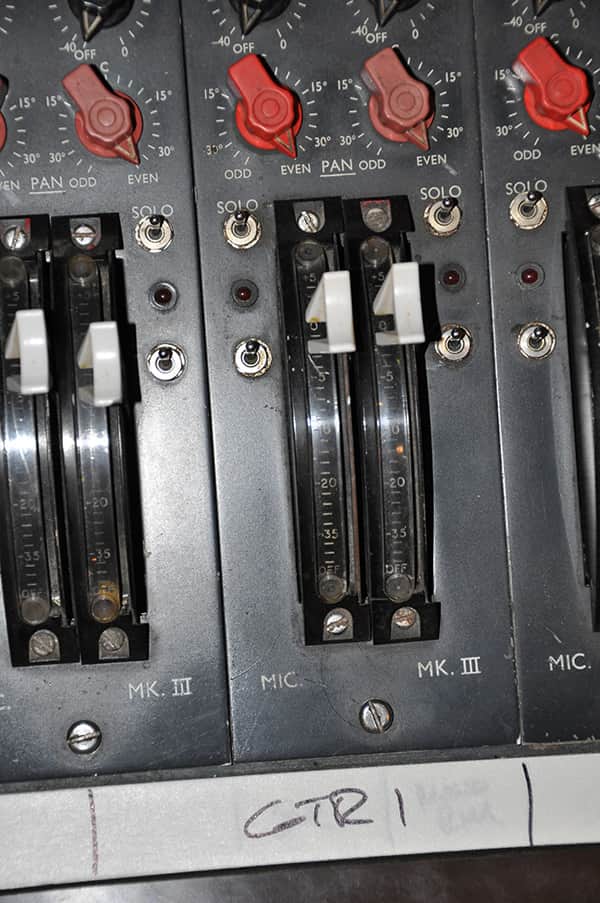

Valentine’s post mic signal paths were remarkably simple: ancient desk into ancient tape machine. “Everything went through the 1972 or 73 EMI TG1 desk that I’d borrowed because my custom made console wasn’t finished yet. The EQ is not hugely flexible, but I could do some basic moves with it. I recorded the band to a two-inch 16-track Scully tape machine, and also edited on that. So editing was all about razor blades and slicing tape. The Scully was crucial to these recordings. It’s a really odd beast with a very specific and very cool sound. Scullys were used on some of the early recordings of Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin, and it was the first piece of equipment I’ve come across where the second I used it I immediately went: ‘There’s that sound! This really sounds like the classic records that I love!’. I heard this more with the Scully than with anything else I’ve used, whether they were mic pres, microphones, EQs, whatever. My Scully is American made from around ’69-’70. I stumbled across it in 2004 and had it refurbished. It’s a cumbersome machine to use because it doesn’t punch in very well and the remote was designed by a crazy person.”

Because Valentine often used several amplifiers for one guitar part, the amount of tracks quickly exceeded 16. Various other instruments, like keyboards, strings, and percussion added to the need for more tracks, so while he used the Scully mainly for the basic bass and drums tracks, he employed a Studer A800 24-track for overdubs. Surprisingly, however, most vocals were recorded to ProTools.

Valentine: “Only Rocco Deluca, Beth Hart and Adam Levine sang directly to tape. For the rest I did a reference mix of the master, transferred that to ProTools and they sang to that. Most singers prefer to sing into a computer, because it’s a lot easier for them. Tape machines suck for singers. Getting everything in tune and in time with all the emotion is really hard to do in one take or one punch and singers are faced with very real endurance issues. They simply can’t scream into a microphone for hours on end.

“Recording in a computer is a lot freer for vocalists. I can record a bunch of passes of the whole song and I don’t have to force them to re-sing specific lines. It allows them to get immersed in the song and they don’t have to think so much about pitch or getting this or that word right, or whatever. I actually get more honest performances from singers when I capture them in a computer. I can then edit their performance, for instance tune a really cool performance, where the emotion is exactly what we want but it’s a tiny bit out of tune in some places. I’ll only nudge things a bit to make sure it’s not distracting, meanwhile definitely making sure everything keeps sounding like real human beings singing. So I never use AutoTune aggressively. It just allows me to use really great, unreproducible but slightly flawed performances. Interestingly, it was the old-school guys that really embraced the computer, with Lemmy saying, ‘aren’t these computers great?’ They’ve lived through the challenges of capturing performances on tape machines and they know how hard it can be. There are times where you lose stuff that you love because you’re trying to punch in one small part or surpass a previous take and it just doesn’t get any better. It can be frustrating and tedious. With the computer, any time someone does something incredible it can be kept.”

Slash… comes up with really cool guitar riffs that you want to hear clearly and he’s capable of playing them in a very cool, aggressive, punchy way. He has a particular attack that’s part of his signature sound and it makes mixing his guitar tracks really straightforward

CURVY TAPE MACHINES

Valentine: “I used RMG’s 911 formula tape during the recordings of Slash’s album, but I wrestled with that the whole time, so the next time I may try ATR tape. My favourite tape used to be 3M 996, and after they stopped making that, I switched to GP9 and occasionally to 456. All the multi-track recordings for the project were done at 15ips with an IEC/CCIR EQ curve, no Dolby. This meant calibrating the machines to what many people call the ‘European’ standard. Early analogue tape machines had more problems with hum, so the circuits had the low-end pre-emphasised which then could be turned down on playback to help minimise the hum. Eventually tape machines got better with less hum issues, and in Europe they came up with a new EQ standard, which is essentially the opposite in that the high end is pre-emphasised so it can be turned down later to minimise hiss, and it also greatly improves the amount of headroom. This standard works much better for 15ips, but most of the American recording scene has remained locked into the original NAB recording curve, because so much material was recorded with it that it was difficult to change. The mix for By The Sword was done on half-inch, 30ips, and that uses a totally different EQ standard called the AES curve on which everyone has settled.”

BY THE SWORD

Artist: Slash, featuring Andrew Stockdale

Writers: Slash/Stockdale

Producer: Eric Valentine

Mixed by: Eric Valentine at Barefoot

Recording in Los Angeles

Eric Valentine: “By The Sword was mostly recorded like I described, with the added benefit that we had the singer available while we were tracking. Andrew came up with a lot of arrangement ideas and contributed to the overall approach of the song. Slash plays an acoustic in the intro, which is a Martin reissue of the classic D28 which I recorded with a pair of Schoeps M221 mics. Whenever I have only one of these available to me I like to place it between the sound hole and the 12th fret, so it doesn’t get too boomy. In this case I had two mics in that position, one looking down at the strings from the top and one looking up from below, so that as you pan them in stereo, the strings actually pan across the speakers a little bit, which is a cool effect. I had the prototype EQ for my custom desk around and any time I needed detailed EQing I used those, and I used them when recording the acoustic guitar for this song. Pretty much all EQ on this album was done by this custom EQ or on the EMI TG1.

“Mixing By The Sword was pretty straightforward because the songs were tracked with the sounds we wanted, so mixing was mostly a matter of balancing and letting the sounds come out unencumbered. Keeping the mix simple was also the only way I could get away with my mix setup, which was really ridiculous. I’d hoped that my custom console would be ready for these recordings, but it wasn’t, so in the interim – while the console was being built – I had set up a 48-channel Flying Faders system using just the faders of my as-yet-unfinished custom desk, and two stereo summing buses. It didn’t have auxiliary sends or inserts, so I had to patch outboard effects in between the tape machine and the faders. In addition I’d use ProTools as a sort of universal effects box. I had duplicates of all tracks in ProTools, so if I needed delay splashes or reverb or whatever in particular places, I could send that to a plug-in, and take a stereo output from ProTools to the fader pack. In some cases I also ran some outboard, like the Ursa Major Space Station and the Eventide H3000 through ProTools, to be able to use the automation and have more control.”

DRUMS

“On this song I had the four drum mics, plus one room and two chamber mics. The drums were as I described earlier: U67 on the kick, 57 on the snare, C12As for overheads, and there’s a Coles 4038 mono room mic, while the two chamber mics are a pair of Neumann KM84s. The drum sound is a balance of those, with a little bit of EQ. The snare drum and mono room had a little bit of my prototype EQ, while the room mic was gated to open when the snare hit, and the snare had some dbx 165A compression. I submixed the drums to a stereo pair, on which I had a pair of Distressors and some NTI EQ and I also did some parallel compression with a pair of 1176 compressors that I mixed underneath to add more density to the ambience.”

BASS & GUITARS

“There are two bass tracks; one D.I. and one recorded with a U47 FET recorded with compression from the EMI desk. I didn’t compress it any more during the mix; I just added some of my prototype EQ. Getting a good guitar sound in a track starts with having a great sound at the source and recording parts that are easy to feature. Slash comes up with both; he comes up with really cool guitar riffs that you want to hear clearly and he’s capable of playing them in a very cool, aggressive, punchy way. He has a particular attack that’s part of his signature sound and it makes mixing his guitar tracks really straightforward. I mean, a 57 sounds great on a Marshall rig, so we used that a lot, and when you have a player like him, it sounds huge. Some of the guitars in the mix had multiple sources – and hence tracks – so I sub-mixed these on the EMI desk, on which I added a Bluestripe 1176 for some additional compression, and from the EMI I sent a stereo pair to my Flying Faders. I also used some EQ, and where there’s reverb, it comes from the room mic. I never sent the electric guitars to a reverb, though I did use some EMT plate reverb, as well as the prototype EQ on the acoustic guitar. There’s another intro guitar, an electric, before the drums come in, which is capo’d and it had an Orban EQ, a BSS dynamic EQ and an LA-2A.”

VOCALS & MIXDOWN

“There are two vocal tracks: one main vocal and a double. I recorded Andrew’s vocals with an RCA 77DX mic and some 1176 compression, and during the mix the vocals went through a pair of modified Altec 436B compressors and a pair of dbx 902 de-essers. The whole mix was compressed with an Al Smart C2, and recorded to half-inch at 30ips. With the mastering we had an initial round that came back too loud with too much limiting. I told the mastering engineer: ‘we’ve gotta turn this thing down about 2dB!’ I think it’s the first time in a while that the mastering engineer has heard that! I can understand that artists get bummed out if their songs sound softer in someone’s playlist where it’s together with other people’s stuff, but limiting for radio makes the least sense because radio stations limit the shit out of everything in any case! I always tell mastering engineers: ‘I don’t care if we have the loudest record, I want it to be the best sounding record.”

On the evidence of Slash, Valentine may have achieved both.

RESPONSES